Letter from the San Fernando Valley — Part Two

Editor’s Note: The first part of this three-part tale of crime and punishment from the second decade of last century ran here last month.

University of Maryland Professor Aryn Phillips and her father, Encino lawyer Mark Phillips, share this updated version of the story first told in their absorbing volume, “Trials of the Century.”

This month: after the horrific murder of a child, a more horrific trial.

Three months after her death, the trial of Leo Frank for the murder of thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan commenced before Judge Leonard Roan on the blisteringly hot Atlanta morning of July 28, 1913. During the course of the trial, the courtroom windows had to be left open, and in addition to the hundreds of spectators in the courtroom, a large and impassioned crowd collected outside to watch and listen. The trial pitted two well-known lawyers against each other. Thirty-two years old and a native Georgian, prosecutor Hugh Dorsey was an ambitious lawyer from a family of lawyers. Since 1911 he had been the Solicitor-General of the Fulton County Superior Court, and thus responsible for the prosecution of Mary Phagan’s accused killer. Bespectacled and intelligent, a series of embarrassing trial losses had nonetheless placed him in a position where a win was necessary to salvage his career. Dorsey’s opponent, fifty-three-year-old Luther Z. Rosser, was at the peak of his career. Portly and old-fashioned, famous for never wearing a tie in the courtroom, he had the deceptive air of a country lawyer, but was considered then the best advocate in Georgia.

The defense strategy was simple: in an era of endemic racial prejudice, no white man had ever been convicted of murder in the state of Georgia solely on the testimony of a black witness. Rosser intended to pick apart the testimony of the prosecution witnesses, and present a parade of character witnesses on Frank’s behalf who would testify to his upstanding reputation and paint a picture of a man incapable of this kind of crime. The prosecution strategy was less clear. Dorsey did not publicly denounce Frank’s Jewish faith or tie that faith to the commission of a crime, but chose to prosecute Frank on the testimony of his principal witness, Jim Conley, notwithstanding serious doubts about his credibility.

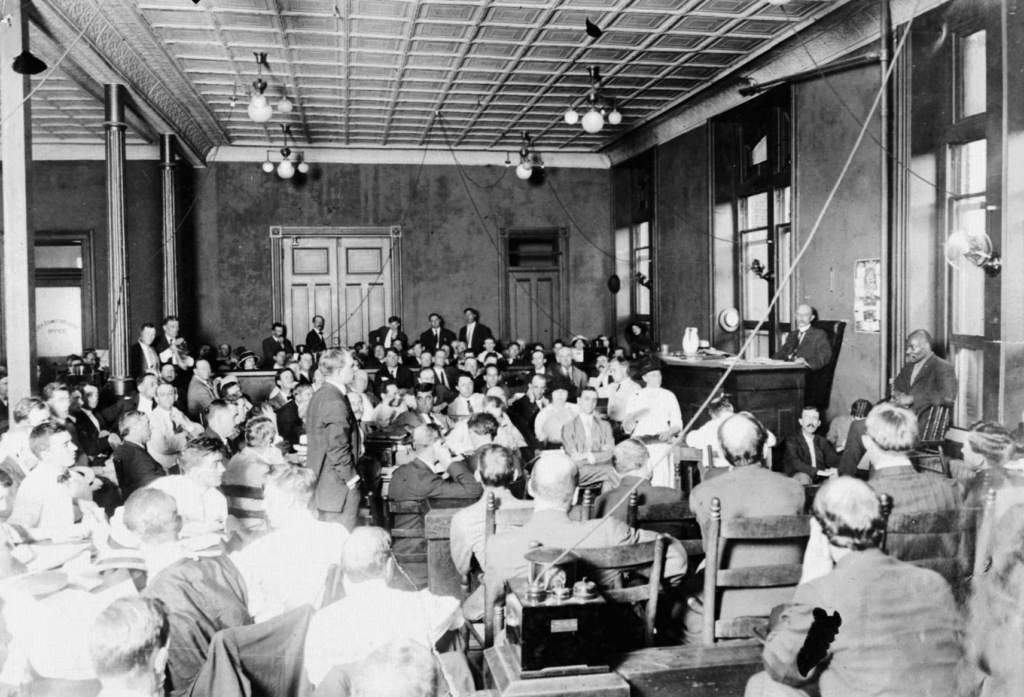

Trial was held in the old Atlanta City Hall, in the room formerly used for City Council meetings. While accommodating hundreds of spectators on three sides, the courtroom was crowded for the parties, attorneys and numerous reporters present to write down every word of testimony and verbal exchanges between the lawyers. The room was also stifling. Photographs of the first day of trial show the many men present having removed their coats and hung them on their chair backs, although the principal lawyers and Frank kept theirs on.

Jury selection occupied the morning of that first Monday, and after lunch the prosecution commenced with the testimony of Phagan’s weeping mother, followed by Mary’s young friend George Epps, and finally the factory’s night watchman, Newt Lee. His testimony was elicited to provide the jury with the physical layout of the factory, the timeline of the murder, and the discovery of Phagan’s body. Over the following days, Dorsey called as witnesses the investigating police detectives, sixteen-year-old fellow worker Grace Hicks, the discharged bookkeeper and initial suspect James Gantt, other factory workers, and the physicians who had exhumed and examined Phagan’s body. Every word of testimony was transcribed by the reporters present, and reprinted for an enraptured public. When the week was finished, the prosecution had demonstrated that Frank had had the opportunity to commit the murder of young Phagan, but not that he had done so.

On Monday morning, August 4th, Dorsey called his star witness, Jim Conley, now washed, shaved, and resplendent in new clothes. Spectators had lined up for hours to get a seat in the courtroom and they were not disappointed by the coming performance.

Dorsey began by asking how he had come to be at the factory on that Saturday. He was there to keep watch for Leo Frank, as he had on prior Saturdays. “For what purpose?” asked Dorsey. “While he was upstairs with young ladies,” came the response.

Conley then held the courtroom enthralled while he recounted his version of the events of April 26th: the arrival of young Mary Phagan, misidentified as “Mary Perkins,” who disappeared upstairs, then waiting for Frank’s summoning whistle, and when it came, Leo Frank’s appearance. “He was standing at the head of the stairs shivering. He was rubbing his hands together and acting funny.”

“What did he say?”

“He says, ‘Well, that one you say didn’t come back down, she came into my office a while ago and wanted to know something about her work and I went back there to see if the little girl’s work had come, and I wanted to be with the little girl, and she refused me, and I struck her and I guess I struck her too hard and she fell and hit her head against something, and I don’t know how bad she got hurt. Of course, you know I ain’t built like other men.’ The reason he said that was, I had seen him in a position I haven’t seen any other man that has got children. I have seen him in the office two or three times before Thanksgiving and a lady was in his office, and she was sitting down in a chair and she had her clothes up to here, and he was down on his knees, and she had her hands on Mr. Frank. I have seen him another time there in the packing room with a young lady lying on the table, she was on the edge of the table…”

This testimony was new and damning. It was unlike anything in Conley’s prior sworn statements, offered a rapacious motive for the killing, implied a deviant sexual character for the superintendent, and described perverse acts that were crimes under Georgia law. Eventually the rest of the story emerged under the prosecutor’s deft questioning. Conley claimed to have found Phagan lying dead on the factory’s second floor, bundled up the body and carried it with Frank’s help by elevator to the basement, and then returned upstairs to write the murder notes. Dorsey was done with him in two hours, and the court adjourned.

When it reconvened, Judge Roan cleared the courtroom of women and children, deeming the testimony too sensational for gentle ears. What followed over the next three days was thirteen hours of cross-examination by Rosser, variously cajoling, quiet, angry, or sarcastic. Frank’s lawyer took Conley through the day’s alleged activities, compared his testimony with the contradictions of his three prior affidavits, all to no avail. When the object of the questioning was new, Conley was brilliantly retentive, adding new and startling details, and by turns apologetic, charming, shuffling, and clever. When Rosser challenged him with the inconsistent statements in his prior affidavits, he claimed not to remember, or simply admitted to lying to officers on the earlier occasions. In the preëminent book on the Frank trial, “And the Dead Shall Rise,” author Steve Oney recounts in riveting detail how Rosser tried time and again to corner the clever Conley, only to have him dance away. “Within an hour, Conley had admitted to a multitude of falsehoods and a dozen times claimed lapses in recall — none of which tarnished his major allegations.” Rosser gave up attempting to trap the sweeper, and by the last day of his testimony simply read the prior affidavits aloud, allowing the jury “to ponder the glaring discrepancies among the various statements.”

All three Atlanta papers reported the testimony of Conley nearly word for word to the impassioned citizens of the city.

When the court reconvened the next day, Judge Roan denied the motion of Frank’s lawyers to strike the sexually explicit parts of Conley’s testimony and the hundreds of spectators in the courtroom burst into applause, hooting and clapping, some shouting the news out the windows to the throngs of onlookers assembled in the streets outside. There was no mistaking the sympathies of the citizens of Atlanta. One more witness was called to testify, completing Dorsey’s presentation of Frank’s guilt, and the prosecution rested.

As damning as Conley’s testimony had been, over the next two weeks Frank’s lawyers orchestrated a thorough and painstaking defense. Rosser and his associates called an astonishing 169 witnesses, presenting testimony on every aspect of the crime, the science, and Frank’s character. The one living person that Conley had identified as an illicit paramour of Frank was called to testify that she didn’t know Frank and had never been in the factory with him. Medical experts challenged the conclusions of the prosecution’s experts as to the time of death and the likelihood of sexual assault. Factory workers present that Saturday testified that they witnessed neither Phagan nor evidence of an assault upon her. They also verified that they had never seen Frank entertain women in the office on Saturdays. Accounting experts reconstructed Frank’s work that day and opined that he had no time to have committed the murder. Minola McKnight, the Franks’ cook, took the stand to repudiate the affidavit coerced from her by the Atlanta police. Local witnesses discredited every element of the prosecution’s timeline, contradicting Conley’s testimony of where Frank was and when. Scores of witnesses from Atlanta and New York swore to the excellent character of the defendant, including friends, family, factory workers, former Cornell schoolmates and instructors, his rabbi, president of the Chamber of Commerce, heads of charities, even one of prosecutor Dorsey’s law partners. Others swore to the disreputable character of the prosecution witnesses. Conley in particular was pilloried by fellow factory employees, both white and black. Physicians were even called to opine that they had examined Frank’s private parts and that he was, indeed, like normal men, contradicting Conley’s most sensational revelation. “I have examined the private parts of Leo M. Frank,” testified Dr. Thomas Hancock, a graduate of Columbia University and Chief of Medicine for the Georgia Railway and Power Company, “and found nothing abnormal.”

On Monday, August 18, 1913, the nineteenth day of trial, Leo Frank took the stand in his own defense. Under Georgia court rules, he was allowed to read a statement without being subject to cross-examination. Throngs lined up to get seats, and hundreds were turned away. Unemotional and cool, Frank spoke for four hours, giving what at times was mind-numbingly tedious detail of the accounting work that he performed in general and on that Saturday that Phagan was murdered. He exhibited little passion, devoting only a few moments in his recitation to the arrival and departure of Mary Phagan as she came for her pay that April afternoon. Coming at the close of the defense’s case, Frank’s statement moved no one, impressed no one, convinced no one. Rosser had apparently not read the superintendent’s remarks in advance.

In closing arguments, the unexpressed prejudice on both sides that had lurked for weeks just below the surface of the trial boiled over. Frank’s attorney recounted the unlikely nature of the circumstantial evidence, summarized the testimony in favor of the defendant, and told the jury, “I tell everybody, all within the hearing of my voice, that if Frank hadn’t been a Jew he never would have been prosecuted. I am asking my kind of people to give this man fair play. Before I do a Jew injustice, I want my throat cut from ear to ear.” Then he publicly accused Conley of the murder of Mary Phagan, describing him in condemnation and derision, “Conley is a plain, beastly, drunken, filthy, lying nigger with a spreading nose through which probably tons of cocaine have been sniffed. But you weren’t allowed to see him as he is.”

Prosecutor Dorsey was in his turn ferociously elegant. He explained away the character witnesses the defense had offered by characterizing Frank as a Jekyll and Hyde. “Dr. Marx, Dr. Sonn, all those other people who…run with the Dr. Jekyll of the Jewish Orphan’s Home, don’t know the Mr. Hyde of the factory.” Of Frank’s religion he said, “This great people rise to heights sublime, but they sink to the depths of degradation, too, and they are amenable to the same laws as you or I and the black race.” Pointing at Frank, his voice rising in power and volume, he intoned:

You assaulted her and she resisted. She wouldn’t yield. You struck her and you ravished her when she was unconscious. You gagged her, and then quickly you tipped up to the front, where you knew there was a cord, and got the cord and in order to save your reputation which you had among the members of the B’nai B’rith, in order to save, not your character because you never had it, but in order to save the reputation of the Haases and Montags and the members of Dr. Marx’s church and your kinfolks in Brooklyn, rich and poor, and in Athens, then it was that you got the cord and fixed the little girl whom you’d assaulted, who wouldn’t yield to your proposals, to save your reputation, because dead people tell no tales.

It was now Saturday afternoon, August 23rd, and with a huge crowd outside and the state militia on call, Judge Roan halted proceedings until Monday morning. The city of Atlanta spent Sunday in hushed expectation. On Monday morning Dorsey finished, re-summarizing the evidence, pitching to the jury as the noon hour neared, telling them “[T]here can be but one verdict, and that is: we the jury find the defendant, Leo M. Frank, guilty!” At that moment, by design or marvelous chance, the bells of the nearby Church of the Immaculate Conception began their mournful count and Dorsey repeated twelve more times, echoing each toll, “Guilty, guilty, guilty…”

By the time the jury began deliberations at 1:35 p.m., a crowd of 5000 prowled the streets outside. Calls to lynch Frank could be heard through the open windows. In the air of hostility against the defendant, Judge Roan and the attorneys agreed that Frank and his lead attorneys should not be present when the verdict was read, as their safety could not be assured.

The jurors took just four hours to come back with a verdict of guilty, and the news quickly spread:

The tumultuous roar echoed from street to street. Trolley cars halted and their drivers and conductors jumped down to join in the jubilation. The result was posted on the scoreboard of the Atlanta Crackers’ baseball game and the grandstand let out a roar. Spontaneous applause broke out at social functions. Hundreds joined hands and danced the cake-walk in front of the pencil factory. The telephone company handled three times as many calls as on any previous day in its history.

The Atlanta newspapers kept pace. The first “extra” edition announcing Frank’s guilt was on the street within three minutes of the announcement of the jury’s verdict.

Prosecutor Dorsey, riding a wave of fame that would carry him to the governor’s house in 1916, on this occasion “…reached no farther than the sidewalk. While mounted men rode like Cossacks through the human swarm, three muscular men slung Mr. Dorsey on their shoulders and passed him over the heads of the crowd across the street.”

The next day, August 25, 1913, Judge Roan sentenced Leo Frank to death.

Next Month: The sentence is carried out, but not by the state.

A Colorado Criminal Defense Lawyer and a Horrific Trial

20 June 2023 @ 2:16 pm

[…] Editor’s Note: What could be worse than the murder of a child (Part 1), or the trial of her accused murderer (Part 2)? […]