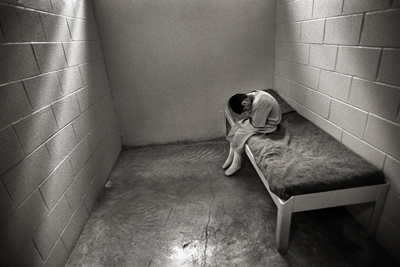

Leave No Child Behind Bars

I’m just a plainspoken Colorado criminal defense lawyer, but the way I see it…

America is the only country in the civilized world, and even in the uncivilized world, to lock up children, and keep them locked up until they are dead. It’s only recently, in fact, that we have stopped ensuring that they are locked up until they are dead, by executing them.

There are a couple of cases now making the rounds of the nine men and women who wear the blackest robes in Washington that might, but I fear won’t, change this. Sullivan v. Florida and Graham v. Florida will decide whether it’s okay by the United States Constitution to give life without possibility of parole to a teenager who’s already experienced life without possibility of full maturation when he or she committed some crime or other.

It didn’t have to be a God-fearing sort of crime to land the youth behind unending bars, either. More than half of them had no prior criminal convictions when they were sentenced. Many were on the periphery of crimes that ended in homicide, but themselves didn’t even carry a weapon: they were lookouts, or doing something else they shouldn’t have been doing, when the murder occurred. One kid in California, when she was 16, killed the pimp who raped her when she was 11 and put her on the street turning tricks for him at 13. Now there’s a child who deserves never to get out of prison.

Seven men, who don’t think it’s right to give up on a human being because of crimes committed as a child, have filed a brief with the Supreme Court in these cases. Every one of them committed some crime as a child that in a different time or circumstance might have qualified them for life without parole. Every one of them redeemed himself. Every one of them believe others may be redeemed.

One of them checked into reform school at 13, and worked his way through progressively tougher joints. He killed another young man in a knife fight when he was 17, and spent a long stretch in prison, some of it in solitary confinement, where he read a play (why not; nothing else much to do in solitary) by Douglas Turner Ward that reawakened his humanity. Charles Dutton is today one of America’s most notable actors and directors.

Another of them burned down a building just for fun when he was in high school; had someone been sleeping in it, now-former United States Senator Alan Simpson, who tells the Court in his brief, “I was a monster,” might have spent the rest of his life in prison.

Another faced a possible life sentence when at 16 he stole a man’s car and wallet at gunpoint. He grew up in prison. He learned how to write there. He’s been out for four years, and R. Dwayne Betts, “not the person I was when I was locked up,” is an award-winning poet.

A fourth started his life of crime a little earlier than high school: Luis Rodriguez was seven when he became a thief. At 11 he was a gangbanger, “willing to shoot, stab and even kill for the gang.” His story of transformation, helped in part by a community that didn’t give up on him, from hopeless case to acclaimed writer, activist, and poet, is told in his brief to the Court.

A fifth stabbed a classmate at age 11 then, for good measure, stabbed the teacher who tried to break up the fight. He was only getting started. How he avoided a life of incarceration to become an Assistant United States Attorney is the subject of Terry Ray’s brief.

Yet another, T.J. Parsell, a software executive, author, and human rights activist, tells a still more harrowing story of his journey from juvenile offender to redemption.

And finally, there is the story of Ishmael Beah, who did things as a teenager far more horrific than any of the rest, and never spent a day in prison. But you should read this one for yourself.

All of their stories, in the brief to the Supreme Court, are here.

Seven stories, seven magnificent stories, of redemption. And sure, in many, many cases of young lives gone wrong, redemption seems only the naif’s hope. But as the rest of the world has already learned, it is always possible. Always.

21 August 2014 @ 4:55 am

There is always a question what punisment a judge shall give to a person who has committed a crime. Where I live and practice (in Iceland) criminals dont get as high jail sentence as in the states. A person who commits murder in Iceland can expect to get 16 years jail sentence. That means he or she will be out in ten to twelve years. That is a long time to be in prison. Everybody can turn their life around if they want to, and get some help. I dont belive that long sentence will reduce crime at all. I at least have never ever defended a criminal who was thinking about what sentence he would get before he committed the crime.

25 June 2014 @ 3:50 pm

Very insightful. Thanks for sharing. Most useful for representatives of children in The Gambia’s children’s court.