Memorial Day

I’m just a plainspoken Colorado criminal defense lawyer, but the way I see it…

I laughed when my mother died. Giggled, actually. I was thirteen and playing some stupid game when my uncle told me she was dead. It’s only now, as I write these words, that I realize it should have been my father to tell me she was dead.

Hearing me laugh, my mother’s brother-in-law said nothing, and began to get ready to drive us home. Shaving his face with an old strop razor, he looked down at me and said it was hard for a man to show he hurt; that he had lost his daddy when he was my age; that it was all right to cry if I wanted. I did cry then, and in that moment loved my uncle more than I had ever loved my father.

I had known she would die. I knew it when she told me she would get better, when she said we’d celebrate when she came back from the hospital. I knew there’d be no coming back, and though she asked me to stay, I went off anyway with my younger brother and sister to our aunt’s. I couldn’t bear to watch her die.

At her funeral, she was laid out in a cheap casket, her face painted like a harlot. I was afraid to look at her; my father said I must. People said she looked peaceful, calm, at rest. She didn’t look like that. She looked dead.

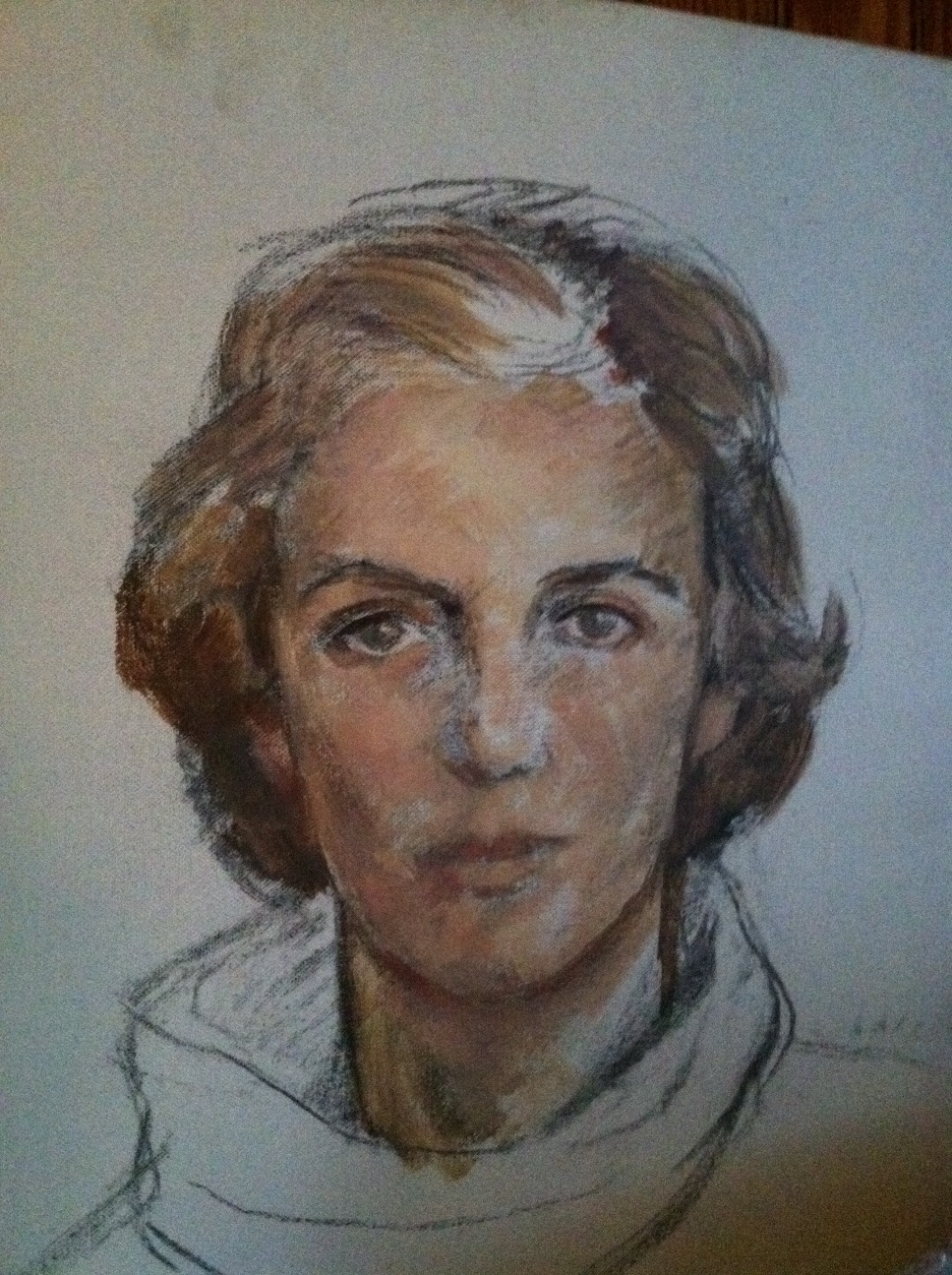

Last week there was another funeral, of another mother. I knew my wife’s mum in a way I didn’t have the time to know mine: as an adult I could appreciate her rowdy and magnificent past, and her rowdy and magnificent present. I will be with her family, my family, to celebrate this singular old sparkler who gave birth to my wife, and the sweet longing for reclaimed innocence to the author of Catcher in the Rye — she was his inspiration for his character, Esmé, a secret she kept out of loyalty to him for sixty years — at her memorial this summer.

But I didn’t want to go to her funeral. I wanted to remember the laughing, vital woman she was.

Because I was still afraid. Still that child, gazing on the rouged dead face of his mother.