That final summer of 1969 had been blisteringly hot in Los Angeles, the kind of days that most residents would prefer spending at the beach, laying by the pool, or sitting beneath blasting air conditioning units. Among those just trying to beat the heat were young Hollywood starlet Sharon Tate, who, clad only in a matching bra and panty set, entertained a few friends at her posh home in the hills above Hollywood, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, a couple returning home from a day spent at Lake Isabella, a popular vacation spot about 150 miles outside the city.

Less concerned with the heat were their killers, who invaded their homes and murdered them in the strangest and most gratuitous of ways. They strung their victims together by rope, masked them with pillowcases, stabbed them dozens of times, and scrawled cryptic words in blood on the walls. This cabal of long-haired, barefooted youths, no older than the local college kids, lived on a ranch not far from the city as members of a cult calling themselves the “Family.” They had been sent to kill these innocent strangers by the persuasive, mysterious and terrifying Charles Manson, whose apprehension and trial combined into the milestone event of 1970.

The murders they committed sent Los Angeles, indeed the entire country, into a tailspin of shock, fear, and fascination with Manson and everything his “Family” stood for, and the trial that followed was the longest and most costly murder trial in American history. Fifty years later, the case remains a topical reference and a subject of cultural significance, even to those too young to have experienced it firsthand. The entire episode has been heralded as one of the most chilling in crime history.

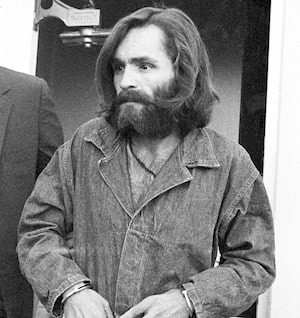

In 1969, Charles Manson was in his mid-thirties. He was small, only 5’2” and slim, with petite facial features and dark brown hair that he wore long and wild, down to his shoulders. His face would soon become one of the most recognized and feared in America. Born November 12, 1934 in Cincinnati, Ohio to sixteen-year-old Kathleen Maddox, he never knew his real father; the name Manson was adopted from one of Kathleen’s later husbands. Kathleen had trouble with the law, and Manson’s early childhood was spent either living with different relatives or, when she was not in prison, moving from motel to motel with his mother and whomever she was dating at the time. When Manson was twelve, Kathleen placed him in foster care.

He spent the next few years bouncing around different facilities, from which he frequently ran away, and getting in his own legal trouble. At thirteen, he committed armed robbery. At sixteen, he drove a stolen car across state lines, a federal offense, after which he was kept in federal institutions. Sometimes he behaved. Other times, he attacked and sexually assaulted the other boys. He was deemed unstable and “safe only under supervision.”

In 1954, then nineteen, Manson was paroled. He worked sporadically as a busboy, service station aid, and parking lot attendant, but he soon resumed boosting cars. He was arrested again in Los Angeles in 1955 and sent to Terminal Island in San Pedro, California. When he was released in 1958, he took up pimping. He was arrested again in 1959 when he attempted to cash a forged check. He was placed on probation, but he quickly violated its terms and returned to prison in 1960.

When he was finally released in the spring of 1967, Manson was thirty-two years old. He had been institutionalized for a total of seventeen years, throughout which he exhibited wild and unpredictable behavior. He had been obsessed at different times with playing guitar, the Beatles, and Scientology, claiming that he had obtained the religion’s highest level, that of “theta clear.” He had been married twice, once to a seventeen-year-old waitress between his release at age nineteen and his arrest in California, which ended in divorce in 1958, and then to a nineteen-year-old prostitute when he was pimping. In 1963, she too divorced him. Each marriage resulted in a son named after him.

Manson had missed the development of the counterculture movement while he was locked up, but he liked what he saw when he was released. He moved north to Berkeley, where he sang, played guitar, and panhandled on the streets of the ultra-liberal college town. There he met Mary Brunner, a twenty-three-year-old college-educated assistant librarian at the university. She was lonely and plain looking but he made her feel special. He moved in with her and lived off her income, inviting other young girls he met to do the same.

In April, he began spending the majority of his time in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, a neighborhood widely known to be a hippie refuge and a place where peace-loving people could find acceptance, cheap rent, and an overabundance of music, drugs, and free love. The neighborhood attracted thousands of young people. Many of these arrivals had a real dedication to the hippie philosophies and political goals of peace and acceptance, but many others were simply aimless wanderers or runaway teenagers, naïve and lonely misfits looking to belong. Of the crowds that swarmed the streets, one previous Haight resident remembers “you can’t emphasize enough the innocence of most of these starry-eyed kids,” that “they were ripe to take advantage of, if anybody wanted to.”

And so the area was also full of sidewalk preachers and gurus, people sermonizing their various ideas on life to anyone who would listen. Manson quickly became one of them. His unique brand of thinking combined Beatles lyrics, passages from the Bible, and Scientology, and, being a talented orator, he explained it all in a charismatic and dramatic fashion. Before long, he had attracted many willing followers, both women and men in their late teens and early twenties, and the Family was born. Some of his adherents were from disadvantaged circumstances, others abandoned paying jobs and supportive parents, but all were lonely, unsatisfied, and troubled, eager to believe and belong.

The Haight soon became overcrowded, with hundreds of young people arriving each day, and Manson tired of it. He packed his followers into an old bus and took to the road. For over a year, the group roamed the coastline from Washington to Mexico, spending much of their time in Los Angeles. They camped, rented, squatted, and stayed with various friends and peripheral acquaintances, including Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, while Manson tried to make it in the music industry. Eventually they settled at Spahn Ranch, a decrepit and isolated ranch outside L.A. that had, in its former days of glory, been a filming location for movies and television shows. Manson continued to recruit followers along the way and within months the Family at Spahn numbered at least thirty-five. The ranch’s elderly owner, George Spahn, allowed them to stay partially because he was unaware just how many members of the Family were living on his land and partially because Manson assigned one of the young girls to take care of him, physically, emotionally, and sexually.

Life under Manson’s rule was bizarrely unconventional. All Family members were expected to turn over their money and personal property to him, but, even so, the group needed more to survive. They scattered into the surrounding area to panhandle, steal, and go on “garbage runs,” in which they took unsold food out of supermarket trash cans. As expected, Family members were constantly arrested for loitering, robbery, and grand theft auto. Manson gave everyone new names, sometimes more than one, depending on what he felt fit their personalities. Meals were communal and no one was served until Manson was seated. Children were separated from their parents and cared for as a group. The Family commonly went on “creepy-crawly” missions, meaning they entered random Los Angeles homes and silently crawled around while the occupants were asleep, moving and rearranging small items. There were countless rules to follow. Wristwatches, calendars, clocks, and glasses were forbidden. Female members were forbidden to carry money. If Manson walked past someone at the ranch, he would make faces and wild gestures and that person was forced to mimic him until he stopped.

Sex with random partners was encouraged to increase the unity of the group, and it was not uncommon for Manson to assign or forbid two people to or from each other. There were orgies that Manson would orchestrate and lead, assigning each person’s position and task. Drugs, particularly marijuana and LSD, were free flowing, although Manson often took less than everyone else when they embarked on communal “trips,” enabling him to retain more control over the situation.

Violence was constant. Manson acquired a large cache of guns and knives and threatened anyone who disagreed with him. He killed, or at least ordered killed, several people, including a Spahn ranch hand named Donald “Shorty” Shea, several defecting Family members, and peripheral hangers on. He shot a drug dealer with whom a deal went awry and left him for dead, though he survived. Manson explained to his followers that fear was beautiful and that the more fear you have, the more awareness you have, thus, the more love you have. He claimed that death was beautiful because people feared death.

The combination of sex, drugs, and fear made Family members not only loyal and submissive to Manson, but somehow made them love and adore him. They never questioned his authority. For the women, sex with Manson was a privilege. One Family member, who eventually defected and provided important testimony during the later trial, remembered how Manson would lead the orgies, explaining that “he’d set it all up in a beautiful way like he was creating a masterpiece in sculpture.” Another member claimed that “Charlie is love, pure love.” It was clear to anyone who spoke to a Family member that he or she would go to the ends of the earth for Manson, many believing him to be the second incarnation of Jesus Christ.

Manson preached often and intensely to his avid followers, and his philosophy, while still loosely based on Beatles lyrics and the Bible, had grown and developed over the years. He believed that the world was on the brink of an apocalyptic race war, which he called Helter Skelter. Blacks would win this war, he claimed, and wipe out the white race. But they were not smart enough to adequately run the world they would inherit, so they would naturally ask for help from him and the Family, who would be hiding out in a “bottomless pit” in the desert. They would hand over the reins of power and Charles Manson would rule the world.

Manson claimed to have found the evidence supporting his theory both in the ninth chapter of Revelation in the New Testament and the White Album released by the Beatles in late 1968. Revelation 9 tells of a bottomless pit in the desert and of five angels, one of which had the key to this bottomless pit. He felt that he was this fifth angel and that the Beatles were the other four. In the White Album, Manson claimed, the Beatles were not only encouraging the start of the race war but were also speaking directly to him. The song “Blackbird,” he explained, with its lyrics “blackbird singing in the dead of night, take these broken wings and learn to fly,” encouraged blacks to rise up. The song “Piggies” was about the rich or anyone belonging to “the establishment.” “Revolution 1” and “Revolution 9” (which Manson thought corresponded with Revelation 9) explained how the upcoming revolution would play out. The song “Helter Skelter” told him of the role he would soon play, and when and how to emerge from the bottomless pit in the desert.

The Beatles never supported Manson’s interpretation of their lyrics. In September of 1970, John Lennon told a member of the press “if I were…a praying man, I’d pray to be delivered from people like Charles Manson who claim to know better than I do what my songs are supposed to mean.” In an interview he gave to Rolling Stone magazine in January 1971 he said “I don’t know what ‘Helter Skelter’ has to do with knifing somebody.” And Manson? “He’s cracked all right.”

Manson believed that the revolution would start with blacks committing heinous crimes in wealthy white neighborhoods of Los Angeles, but no such crimes were occurring. Manson became anxious, upset by Helter Skelter’s slow progress, and decided to get the revolution started himself. The best way for him to do so, he believed, would be to commit a terrible and upsetting murder in a white neighborhood and make it look as if it had been perpetrated by the black community. Such a crime would spark animosity between the races, ignite the revolution, and, as explained by a former Family member, “show blackie how to do it.”

On the night of Friday, August 8, 1969, Manson gathered some of his most loyal followers and instructed them to dress in dark clothing and find their knives. Among those chosen was twenty-one-year-old Susan Atkins, a short brunette named Sadie Mae Glutz by Manson who had been with the Family since November 1967. The product of a troubled home, Atkins dropped out of school at sixteen, worked as a topless dancer, experimented with drugs and satanic worship and was arrested for armed robbery, all before meeting Manson. Also chosen was twenty-one-year-old Patricia Krenwinkel, called Katie, a dark-haired girl from Los Angeles who left her job as a process clerk for an insurance company to join Manson, and twenty-three year old Charles Watson, called Tex, former high school jock, college dropout, and Manson’s right hand man. The final member of the cabal was Linda Kasabian, a twenty-year-old who had been on her own since age sixteen and had spent the past few years living in communes and experimenting with drugs. A relative newcomer to the Family, she had only been living with Manson for about a month but was asked to join the mission because she was the only member of the Family with a valid driver’s license.

Manson gave explicit instructions to Tex and told the others to obey his orders. The four set out from Spahn ranch and drove to a home on Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon, the area above Hollywood and Beverly Hills. The house belonged to a man named Rudi Altobelli and was being rented by famous movie director Roman Polanski and his beautiful wife, twenty-six-year-old actress Sharon Tate. The Polanskis, however, had spent much of the summer in Europe, so the house was being tended to by their friend, twenty-five-year-old Abigail Folger, heiress to the Folger coffee fortune, and her boyfriend, thirty-two-year-old Wojiciech “Voytek” Frykowski. Tate had returned from Europe a few days prior and was staying at the house with Folger and Frykowski until Polanski came home. Manson and Watson had been to this house before. Dennis Wilson had once introduced Manson to the house’s previous occupant, Terry Melcher, record producer, son of Doris Day, and boyfriend of Candice Bergen. Melcher had declined to sign a contract with Manson, but Manson chose the house not out of revenge but because he knew it would be isolated.

The group arrived at the house after midnight, cut the telephone lines, climbed the gate, and slaughtered everyone inside. Afterwards, they got back in the car, changed clothes, tossed their bloody garments and knives over the side of the canyon, and drove back to Spahn Ranch.

The murders were discovered the next morning when the housekeeper, Winifred Chapman, arrived and, upon seeing a body, telephoned the police. The officers arrived sometime around nine A.M. and found themselves at a crime scene unlike any other they had seen before. On the front lawn they found the bodies of Frykowski and Folger. Frykowski had been shot twice, hit repeatedly in the head with a blunt object, and stabbed fifty-one times. Folger had been stabbed twenty-eight times, her once white night gown completely stained with blood. Inside, they found the body of eight-month pregnant Sharon Tate, stabbed sixteen times. Also in the room was the body of Jay Sebring, hair stylist to the stars and Sharon Tate’s close friend. He had been shot once and stabbed seven times. Sharon lay in the fetal position and Jay looked as if he died trying to ward off future blows. In the driveway, slumped in the driver’s seat of a white Rambler, they also found the body of eighteen-year-old Steven Parent, who had been shot four times. Unconnected with Tate or any other of the victims, Parent, a Los Angeles local who had just recently graduated from Arroyo High School, had been visiting William Garretson, a young man Rudi Altobelli had hired to live in the back house and take care of the property while he was away.

If the carnage and savagery of the murders were not enough, the scene itself was bizarre and grotesque. Tate and Sebring had been tied together by a rope that had been strung over a ceiling rafter and looped around their necks. A blood-stained towel had been thrown over Sebring’s face. The word “PIG” was written on the front door in blood.

News of the murders spread quickly and investigations began immediately. But back at Spahn Ranch, Manson was unhappy with how the events of the previous evening had unfolded. He felt that it had been “too messy” and prepared his team to strike again that night. This time, they were joined not only by Manson himself but also by Leslie Van Houten and Steve Grogan. Twenty-year-old Van Houten had gotten hooked on LSD at age fourteen and moved to the Haight. At one point, she finished high school, took a year of secretarial courses, and began training to be a nun, but she dropped out, took up drugs again, and lived on a commune until meeting Manson. Grogan, an eighteen-year-old known to the Family as “Clem,” had been arrested countless times and was diagnosed by psychiatrists as “presently insane.” Sentenced to a stay at Camarillo State Mental Hospital, he had managed to escape with help from the Family. Together, they drove through Pasadena and east Los Angeles. Manson gave directions and looked for a random home to target, passing over his first few choices because he saw pictures of children in the window and because the houses were too close together.

Eventually, he settled on a home in Los Feliz belonging to Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. Leno, age forty-four, was the president of a local grocery store chain, and his thirty-eight-year-old wife Rosemary, to whom he had been married for ten years, owned and operated a successful clothing boutique. Rosemary had two children, aged fifteen and twenty-one, from a previous marriage. Manson entered the home alone, tied up the couple, and returned to the car. Watson, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten then entered, murdered the LaBiancas, and hitchhiked back to Spahn Ranch. Manson, on his way home, stopped for milkshakes.

The bodies of the LaBiancas were discovered the following evening by Rosemary’s children. The police, upon arrival, found a scene equally if not more shocking than the one at the Tate residence. Leno was in the living room, a pillowcase over his head and a lamp cord wrapped around his neck. His hands had been tied behind his back. He had been stabbed twelve times with a knife and an additional fourteen times with a two-pronged kitchen carving fork, which was left protruding from his abdomen. The word “war” had been carved into his skin. Rosemary’s body was found in the bedroom. She had been stabbed forty-one times in the back and legs and, like her husband, a pillowcase had been placed over her head and a lamp cord wrapped around her neck. The words “DEATH TO PIGS” and “RISE” were written in blood on the living room walls and “HEALTER SKELTER” incorrectly spelled out in blood on the refrigerator door.

The Los Angeles Police Department immediately began their investigations, but it took a long time for them to connect the two murders to the Manson Family, or even to each other. Assigned to separate LAPD investigative teams, the Tate investigation was led by Lieutenant Robert Helder and his team, while the LaBianca case was covered by Lieutenant Paul LePage and an entirely different group of detectives.

Several theories circulated about the Tate murders. Cocaine and marijuana had been found among the victims’ possessions, leading some to believe that the murderous rampage had been the result of a drug trip gone wrong or a drug deal turned violent. Another promising theory was that William Garretson, the groundskeeper, was behind the killings. He was found that morning in the guest house and claimed to have heard or seen nothing unusual the night before. He was arrested and questioned but was eventually cleared of suspicion. The LaBianca detectives were operating under the suspicion that the murders had been the result of an upset robbery. Two months after the murders, neither team had made much headway.

On October 15th, the LaBianca team asked the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Office if it was investigating any other murders that might be similar to the LaBianca case. LASO officers told their LAPD colleagues about the murder of Gary Hinman, a thirty-four-year-old music teacher who had been found dead in a home in Malibu in July. He had been stabbed to death and the words “POLITICAL PIGGY” had been written on the wall in blood. LASO had arrested a suspect, Robert “Bobby” Beausoleil, shortly after. Beausoleil had been in custody since August 6th so he could not have been involved in the LaBianca murder, but prior to his arrest he had been living at Spahn Ranch with Manson. Spahn Ranch had been raided in August and several Family members had been arrested as suspects in an auto theft ring.

Following the August raid, Manson had moved the Family to Barker Ranch, an extremely remote and isolated homestead near Death Valley. Barker Ranch was raided in early October and twenty-four Family members, including Manson, were arrested on a wide variety of charges. They were being held in jail in Inyo County, about five hours outside of Los Angeles, still unconnected to the Tate and LaBianca murders.

During the raid, Inyo County law enforcement had come across two young girls attempting to flee the Family. One was seventeen-year-old Kitty Lutesinger, Bobby Beausoleil’s girlfriend. Lutesinger remembered hearing that Susan Atkins had also been involved in the Hinman murder. Atkins, arrested in the Barker Ranch raid and being held in Inyo County, was questioned, booked for suspicion of murder, and moved to Sybil Brand Institute, a women’s detention center in Los Angeles. There she was placed in a cell with two former call girls: Ronnie Howard, in jail for forging prescriptions, and Virginia Graham, arrested for violating her parole. Atkins was talkative in jail, and she told her cellmates all about life with Manson. She also told them about killing Hinman, and eventually, that she had killed Sharon Tate and her guests, and that her friends had killed the LaBiancas. Howard would remember her saying that it “felt so good the first time I stabbed [Sharon Tate]” and that “the more you [murder], the better you like it.” She bragged that she and the Family were responsible for eleven murders that police would never solve and that there would be more to come.

A scared and concerned Howard told on Atkins. Taken out of Sybil Brand for a court appearance on November 17, she telephoned LAPD, claiming to know who had committed the Tate murders. That evening, two officers came to Sybil Brand and interviewed her, placed her into protective custody, and brought the news back to headquarters. They were convinced that she was telling the truth; Akins had told of several details that were known only by the police and the murderers.

Lutesinger had also told authorities that Manson had attempted to recruit members of the Straight Satans, a motorcycle gang, as bodyguards. On November 12, a gang member, Al Springer, was picked up and questioned on an unrelated matter, and the LaBianca detectives took the opportunity to interview him about Manson. Springer never joined Manson’s Family but he did remember Manson bragging about killing five people and about writing on a refrigerator in blood.

Springer also directed the police to Danny DeCarlo, a member of the Straight Satans who had spent a great deal of time at the ranch with Manson. DeCarlo confirmed Springer’s story. He remembered Clem bragging to him about killing five “piggies.” He recalled that Manson had a favorite gun that had disappeared after the weekend of the murders and, knowledgeable about firearms, he was able to draw a picture of the weapon. Pieces of a broken and bloodstained gun handle had been found at the Tate residence, and DeCarlo’s drawing was an exact match to the gun to which these pieces belonged. Finally, he described a certain kind of rope kept at Spahn Ranch, which matched the rope used to tie up Tate and Sebring.

Having implicated herself, Atkins was charged with the Tate murders, and the case was assigned to Deputy District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi and head of the Trials Division Aaron Stovitz. Thirty-five-year-old Bugliosi was an experienced and confidant prosecutor who had been practicing with the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office since 1964. He had tried 104 felony cases and lost only one. Stovitz would be taken off the case for inadvertently violating a gag order shortly after the trial began and replaced by District Attorneys Donald Musich and Steven Kay, but Bugliosi remained the chief prosecutor for the duration of the trial and played an active role in the investigative processes. Richard Caballero, a former district attorney who had gone into private practice, was already representing Atkins in the Hinman case and would now represent her in the Tate case as well.

Slowly but surely, LAPD identified the remaining murderers. Interviews with other Family members exposed Watson, Krenwinkle, and Kasabian as those present at the Tate residence, and warrants were issued for their arrests. Watson was found in his home town of McKinney, Texas, Krenwinkle was arrested in Mobile, Alabama, where she had been staying with family, and Kasabian surrendered to law enforcement in Concord, New Hampshire. Interviews with Atkins exposed the involvement of these three, plus Manson and Van Houten in the LaBianca murders.

In light of the evidence, attorney Caballero struck a deal with the District Attorney’s office on behalf of Atkins that, in exchange for testifying against the other Family members, the DA would not seek the death penalty against Atkins. On December 5, Atkins testified before the grand jury, explaining in detail the events of those two gruesome nights. The jury was shocked not only by her story but also by her frigid, emotionless, and entirely remorseless telling of it. When asked to identify a picture of Steven Parent, the eighteen-year-old found in the white Rambler at the Tate house, she confirmed “that is the thing I saw in the car.” Only after being asked by Bugliosi if “when you say ‘thing’, you are referring to a human being?” did she respond “Yes, human being.” Her testimony was so chilling that one of the jurors had to ask to be excused for a few minutes. While Manson himself had not personally committed any of the murders, it was clear from the testimony that he was the mastermind behind them and that he had a powerful hold over the minds and motivations of his followers. When the grand jury returned after deliberating for only twenty minutes, they delivered indictments for murder against Watson, Krenwinkel, Atkins, Kasabian, Van Houten, and Manson. Kasabian and Krenwinkel were returned to Los Angeles to stand trial and Van Houten and Manson were brought down from Inyo County, where they had been jailed since the Barker Ranch raid. Watson fought extradition from Texas and ultimately had to be tried separately at a later date.

As the investigation continued, physical evidence against the Family members began building up. A print found on the front door of the Tate house was identified as belonging to Tex, and one found on the inside of the French door in Sharon Tate’s bedroom was matched to Krenwinkel. A broken gun found months earlier in the backyard of a home below Benedict Canyon was identified as the gun used at the Tate residence. It was covered in blood of the same subtype as Sebring, and the broken pieces of gun grip found in the house fit its broken handle perfectly. Bullets found at Spahn Ranch were also definitively traced to this gun. Rosemary LaBianca’s wallet was found in a service station restroom, where it had been left by Kasabian, just as Atkins had described. A television crew, attempting to reenact the events of Friday August 8, found Watson, Kasabian, Krenwinkel, and Atkins’ bloody clothing where they had pitched it off the road and into the hillside. Finally, interviews with several other past and present associates of Manson brought to light his philosophies on “piggies” and “Helter Skelter,” the words written at the two residences.

[Next month, in Part II: the trial.]