He Sees Dead Men Walking

I’m just a plainspoken Colorado criminal defense lawyer, but the way I see it…

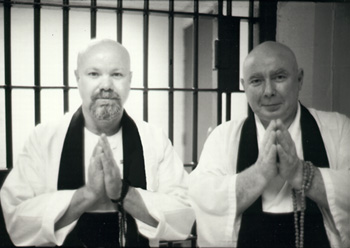

Kobutsu (born Kevin) Malone is a Zen Buddhist priest who has twice watched what no one should ever watch: the legal execution of a friend.

Two front row seats to horror. Each a gift, a willingness to be a loving presence in a roomful of people who want to see you die.

Kobutsu notably witnessed the death of William Parker. I don’t want to say Parker is the only one, but Arkansas in particular, and the United States in general, can’t have executed all that many Zen priests. Parker wasn’t a priest when he murdered his former mother- and father-in law, and he wasn’t a priest while he enjoyed punching the occasional prison guard in the mouth while biding his time toward execution. But one of those guards, when Parker insolently demanded a Bible, thought it was funny to toss instead a Buddhist tract into his cell. Turned out Parker could read, and what he read transformed him.

When Kobutsu met the man, he had already turned himself into a Buddhist scholar whom even some of the guards called Sifu (master), and his cell into a temple. Parker was the only practicing Buddhist in the Arkansas correctional system — not surprising in the Bible Belt, where a Missouri prison guard I met told me the only Buddhist he ever knew was under his safekeeping.

Kobutsu didn’t have even a Christian’s prayer of saving Parker from the death penalty. The Dalai Lama had already tried. Richard Gere had already tried, at least to speak with Parker, but was turned away when the warden pleaded no time for a background check on the actor; he apparently hadn’t seen “Pretty Woman.”

The old governor had no time for Kobutsu, because the old governor was trying to avoid doing time himself for federal felony convictions. And new Governor Mike Huckabee — himself a reverend (though the kind whose reverence for life makes a little allowance to strap down bad guys and stick the needle in ’em) — had no time for Kobutsu because God had already talked the governor into moving up Parker’s execution a few weeks and get the job done good right then.

[I believe God does speak to Governor Huckabee: it’s the only reasonable explanation for that voice in his head.]

Four days before the state killed its prisoner, Kobutsu formally ordained Parker a Zen Buddhist priest. Another probable first. First priest of any faith to be ordained while in shackles. Kobutsu draped a priest’s vestment over Parker’s head. Buddhist priests receive ordination names: Parker became Jusan.

The day of the execution, a bunch of guys dressed like the negative images of George Lucas’s Imperial Stormtroopers arrived to escort Jusan from his cell — down a hall lined with more of the same — to the death chamber.

Kobutsu and Jusan were permitted a final moment together. Says Kobutsu:

I looked directly into his face; I saw a single tear glisten as it rolled from his right eye down his cheek. I could see every pore of his skin, each individual hair in his goatee, the colors of those hairs in a salt and pepper mix. I saw his wonderful smile; I could feel waves of tremendous gratitude pouring from his heart. Time stopped. There was only Jusan and Kobutsu, two old friends saying good-by at the end of the road. No one else was present in all creation at that moment, time dilated to an infinite degree…we are still there, saying good-by, forever…

We embraced, he whispered in my ear, ‘I love you my brother, thank you so much.’ I took one step backward and we did an ‘unauthorized’ bow to each other – as we bowed, our foreheads touched. The impact of forehead on forehead was the last contact we made; it was shocking to me; it was an unexpected contact; neither of us had planned, yet it somehow was incredibly apropos.

On his way to the viewing room, Kobutsu saw outside the building the hearse waiting to carry his friend. His last sight of him was in the stunning bright light of the death chamber, his head and body restrained to immobility, his eyes closed. Though a white sheet almost completely covered the body, Kobutsu could see the straps of another garment: the prison director had allowed Jusan to die in his new vestment, a breach of prison protocol. It took but three minutes.

Kobutsu witnessed a second friend die by execution nearly seven years later. Seven more years of working in the criminal justice system had radicalized him. He called the first execution a killing. He calls the next one, a murder…a lynching.

At this one, at Florida State Prison, the warden would allow no final hour visit with the priest for Amos King, though Kobutsu served as spiritual advisor to the condemned. No final picture of the two of them, a black man served by a white man, together. No final Buddhist bow goodbye.

On King’s last day, they were allowed, through cell bars that separated them, to perform the refuge ceremony, a rite that initiates one into the Buddhist practice. It is an invitation to, and acceptance of, the teacher, the teachings, and the community of practitioners. The ceremony was brief.

King, who had been convicted of raping, stabbing, and leaving an old woman to die in her house he set afire (she did not die of the fire but of the wounds, and was found dead in the doorway trying to crawl from the flames), asked Kobutsu if there were some sort of Zen memorial service. There was, Kobutsu replied, but it was in Japanese. King said he didn’t have time to learn Japanese. Kobutsu said there was a short chant in English, and they did that. Amos King and Kobutsu Malone hugged each other through the bars and that was that.

An hour and a half later Kobutsu saw King on the familiar gurney, with the familiar restraints, under the familiar bright light. King raised and twisted his head to nod at the priest; to Kobutsu it looked like a bow, and he bowed back from his seat. King continued to strain to see who had gathered for the show.

King was allowed a final statement from his back; he asserted his innocence. He looked directly at Kobutsu and thanked him. “That’s it,” he said. Kobutsu watched, again for only a few minutes, until his friend’s chest stopped moving, until two doctors confirmed the heart had stopped moving too.

Neither of the executions Kobutsu witnessed produced drama beyond the workman efficiency of the state executioners. No prolonged agonies; no bulging eyes; nobody bursting to flame.

Just a human life taken in the course of ordinary business. Witnessed by another human life, an extraordinary business.

A candle, snuffed. Another, sputtering.