Letter from Gainesville

[Editor’s Note: Paul Magnarella is professor emeritus at the University of Florida who has worked with the United Nations Criminal Tribunals. He is a lawyer who for years tried to overturn what he says was the wrongful conviction of a member of the Black Panther Party who fled the United States and has lived in exile in Tanzania for fifty years. He generously offers here a taste of that tale, fully digested in his newest book, “Black Panther in Exile: The Pete O’Neal Story.”]

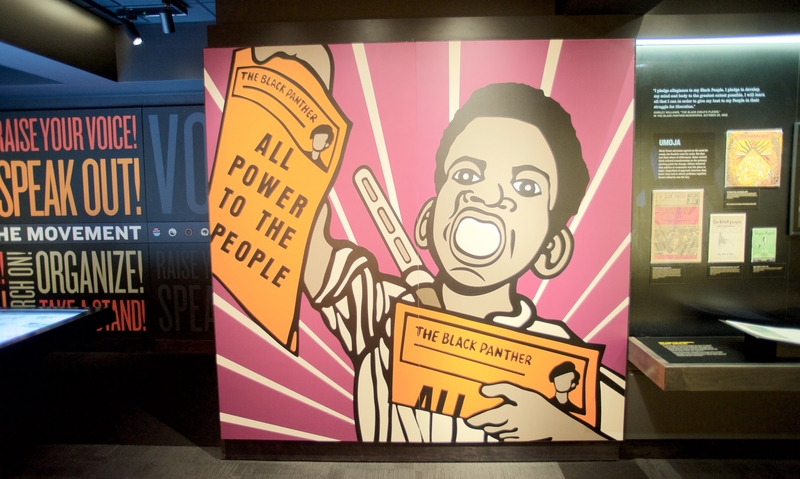

“We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.”

This demand did not follow the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020. Rather it preceded that horrific event by over 50 years; it was Point 7 of the Black Panther Party’s 1967 Ten Point Program.

During the summer of 1967, over 100 US cities erupted into violence, fueled by pent-up resentments in urban black communities over police brutality and other forms of racial injustice. In response, President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized a blue-ribbon commission to investigate the causes of the urban upheavals and to offer recommendations. The resulting March 1968 report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner Commission, concluded that the country was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.” Unless conditions were remedied, the commission warned, the country faced a system of apartheid in its major cities. The Kerner Commission urged legislation to promote racial integration and to enrich inner cities, primarily through job creation, job-training programs, and decent housing. The report also recommended that municipal governments hire more diverse and sensitive police. But just as the report highlighted the inequality experienced by urban blacks and pointed to police brutality as a main cause of the uprisings, the Johnson administration ignored its recommendations and doubled down on a law-and-order agenda.

Felix “Pete” O’Neal, the main subject of “Black Panther in Exile,” grew up in a country that disadvantaged its black inhabitants, first as slaves and then as citizens. Pete spent his youth and young adult years in an impoverished, racially segregated section of Kansas City, Missouri. Growing up during the height of America’s civil rights era, he experienced and witnessed the kind of police brutality that was reserved for the underprivileged.

Kansas City, Missouri, in the 1960s resembled the apartheid situation depicted by the Kerner Report. Racial integration at any level was rare. Neither the city’s prestigious social clubs nor the important trade associations had a single black member in 1968. Black males on average earned 20 percent less than their white counterparts, and about 20 percent of blacks with an elementary-school education were unemployed. The racial inequalities in urban housing, education, and employment were paralleled by racial inequalities in arrests, incarceration rates, and deaths due to police actions.

When poor, disadvantaged people break the law out of economic desperation, comfortable middle-class society often faults them for “making bad choices.” In reality, these people had too few “right choices.” Owing to structural racism, the number of realistic opportunities available to many of the underprivileged fell grossly short of their needs.

Pete was fourteen years old when the US Supreme Court held that racial discrimination in public schools was unconstitutional (1954). He was twenty-seven when the Supreme Court finally invalidated apartheid laws that criminalized interracial marriages (1967). That was followed in 1968 by the assassination of Martin Luther King by a white racist. One year later, O’Neal joined the Black Panther Party, becoming deputy chairman and founder of its Kansas City Chapter. Pete and his fellow Panthers initiated free breakfast programs for inner city youths, free clothing and free medical care for the needy. They also monitored police patrols in the black neighborhoods, hoping to prevent police brutality towards residents.

Pete soon became a victim of the government’s unconstitutional electronic surveillance and a target of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms agents, local police, and the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program), which was designed to destroy the Black Panther Party. On October 30, 1969, ATF agents arrested O’Neal, accusing him of having transported a shotgun across a state line some nine months earlier. After being convicted in a trial that involved judicial errors, serious constitutional rights violations, and perjury by key prosecution witnesses, and receiving threats on his life from local police, Pete and wife Charlotte fled to Algeria and then to Tanzania where they have lived ever since.

Many hundreds of Americans have called for O’Neal’s free return to the United States. As his attorney, I filed petitions with the US District Court in Kansas documenting the constitutional irregularities in Pete’s original trial and requesting a new, fair trial. Unfortunately, that court has refused to recognize its own errors and its mockery of justice. Consequently, O’Neal remains in Tanzania, unable to return to his country of birth, without going to prison for a wrongful conviction. He is one of the last Black Panthers in exile.

In Tanzania, Pete and Charlotte have called on the spirit of the Panther to record enormous achievements for the people of Tanzania and for non-Tanzanians whose lives they have touched. “Black Panther in Exile: The Pete O’Neal Story” weaves personal, historical, and legal stories together to show how the human spirit, even after being assaulted by the state establishment, can survive and flourish.