Letter from Los Angeles — Part Two

Editors Note: This is the second and final excerpt, updated by the authors, from their book “Trials of the Century,” which details the horrific murders of actress Sharon Tate, heiress Abigail Folger, and seven others unfortunate enough to have captured the attention of the madman Charles Manson, who stood trial for his crimes fifty years ago. In Part One last month, Los Angeles lawyer Mark Phillips and his daughter, behavioral scientist Aryn Phillips, wrote of the murders.

This month: the trial.

The trial of Charles Manson and the girls was bound to be a challenging one. The prosecution would have to prove not only that Linda Kasabian, Patricia Krenwinkel, Susan Atkins, and Leslie Van Houten had committed the murders but also that Manson, indicted under conspiracy laws, had compelled them to do so. The “vicarious liability” rule of conspiracy states that a conspirator in a crime is responsible for all the crimes perpetrated by his co-conspirators even if he was not present at the scene and did not physically commit them. The prosecution would have to show that Manson had engineered these murders and that he had used his powerful control over his followers to get them to perpetrate them for him.

All the defendants other than Watson were to be tried together, and their defense team was made up of a rapidly revolving cast of diverse characters. Manson’s case was initially assigned to attorney Paul Fitzgerald of the Public Defender’s Office but, on December 17, almost immediately after being indicted, Manson requested permission to act as his own attorney, claiming that “there is no person in the world who could represent me as a person.” After an experienced third-party attorney judged him mentally competent, the presiding judge, William Keene, had no choice but to approve Manson’s request.

Manson, however, used his newly acquired position not to build a credible defense but instead to make outrageous motions and requests. He asked that copies of every document related to the case be made and delivered to his jail cell. He asked that he be allowed freedom to travel outside of prison. He asked for the names, telephone numbers, and home addresses of every prosecution witness. Finally, in March, when he asked that the prosecuting attorneys be jailed under conditions similar to his own, Judge Keene revoked his privileges, in response to which Manson screamed “there is no God in this courtroom!”

The judge next assigned Manson’s defense to attorney Charles Hollopeter, but, displeased with some of the motions he made, Manson quickly had him replaced with Ronald Hughes. Thirty-five years old, Hughes was often referred to as a “hippie lawyer.” Large and burly, he was balding but sported a long, unkempt beard, and mismatched suits that he bought for a dollar apiece from the MGM wardrobe department. He was well acquainted with counterculture, enjoyed hiking and the great outdoors, admitted having experimented with drugs, and lived in a friend’s garage. He had never tried a case before.

In April, Manson filed an affidavit of prejudice against Judge Keene, and the case was reassigned to Judge Charles Older. A former World War II fighter pilot, Older had developed a reputation as a no-nonsense judge since his appointment to the bench three years earlier.

Only two weeks before the trial’s opening day, Manson asked Judge Older to reassign his case yet again. If he could not act as his own attorney, Manson proclaimed, he wanted to be represented by Irving Kanarek, a well-known although not necessarily well-respected Los Angeles attorney. A stocky man with wavy hair, thick eyebrows, and a slightly receding hairline, it was rumored that he wore a new suit on the first day of each trial and continued to wear it every day until the trial was over. A notorious obstructionist, Kanarek was widely recognized for his excessive use of objections and other delay tactics. On one occasion, he objected to a witness stating his name, because, having originally heard it from his mother, it was hearsay. On another, he managed to delay a trial for so long that a year and a half after its inception a first witness had yet to be called. After two years, the prosecuting attorney chose to retire rather than finish out that trial. Manson was well aware of Kanarek’s reputation and he claimed that, if he could not represent himself, his “second alternative is to cause you as much trouble as possible.” Older approved Manson’s request and Hughes was replaced by Kanarek.

Meanwhile, Manson was using his power to influence the other defendants and their choices of attorneys. Family members constantly visited Atkins in prison and ferried messages back and forth between her and Manson. In late February, feeling the pressure, Atkins claimed that she had changed her mind and refused to testify at the trial. In March, capitalizing on the privileges afforded him by self-representation, Manson arranged an in-person meeting with Atkins. The next day, Atkins fired her lawyer Richard Caballero and asked that he be replaced by Daye Shinn, an immigration attorney who had visited Manson in prison over forty times, hoping to be put on the defense case. Shinn, forty years old and of Korean descent, was new to criminal proceedings.

Krenwinkel requested as her attorney Paul Fitzgerald, the very first attorney assigned to Manson. The Public Defender’s Office felt that this assignment constituted a conflict of interest, but Fitzgerald was anxious to be a part of the defense team. He resigned from the office and went into private practice, taking Krenwinkel on as his only client. Tall and slim, with dark curly hair, Fitzgerald was a knowledgeable and experienced defense attorney, having represented almost four hundred people with the Public Defender’s Office, only one of whom had been sentenced to death.

Van Houten went through what was perhaps the longest sequence of attorneys. Her case was first assigned to Donald Barnett, whom she asked to be dismissed after he ordered she undergo a psychiatric evaluation. Her case was then passed to Marvin Part, who made the same mistake. Despite his protestations that Van Houten “has no will of her own left” and “doesn’t care whether she is tried together and gets the gas chamber, she just wants to be with the Family,” Van Houten’s case was transferred to Ira Reiner, an attorney who had met with Manson several times and whom Manson suggested Van Houten request. Reiner lasted eight months, until jury selection, when it became clear that he was trying to separate her defense from that of the rest of the Family. Van Houten had him replaced by Ronald Hughes, the former Manson attorney.

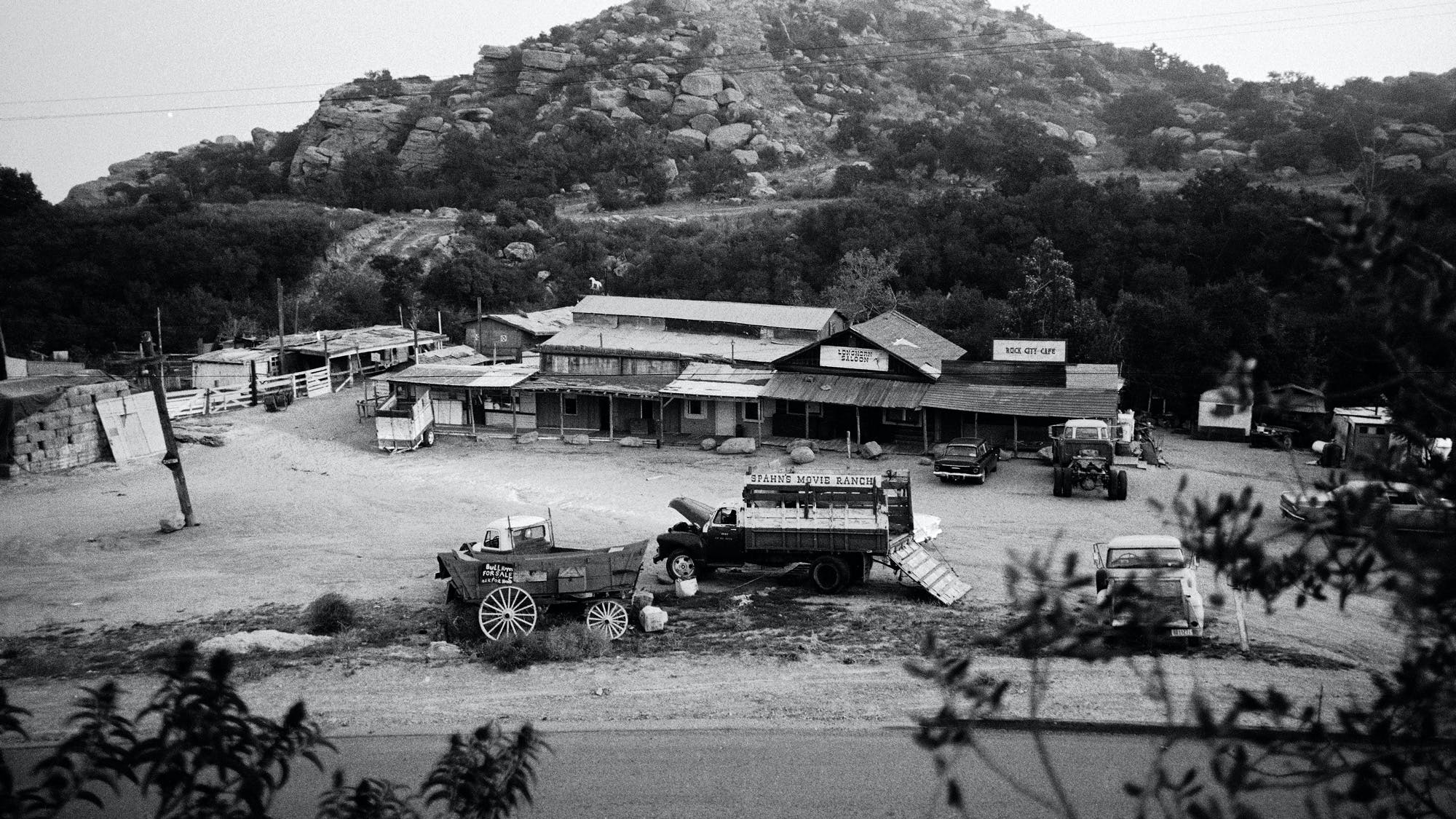

Kasabian was represented by Gary Fleischman, who made it clear from the start that his client was willing to cooperate with the prosecution. She had been the driver, and claimed that she had not actually killed any of the victims, that she had been told to stand guard outside on the first night and had never entered the house on the second night. She had been new to the Family at the time of the murders and she felt badly about what had happened. While she openly admitted that she loved Manson, she claimed to have only cooperated in the murderous rampage out of fear for the safety of her daughter who was being cared for back at Spahn Ranch. She was clearly different from the other girls, who struck outsiders as either deceitful, naïve, or simply insane. Kasabian was polite, truthful, more grounded, and seemed genuinely devastated by what had transpired. When Atkins reneged on her promise to testify in court, the prosecution team dropped its end of the bargain, sought the death penalty for Atkins, and turned to Kasabian, promising to petition the court for immunity if she testified at the trial. Despite threats made to Fleischman by Family members that “if Linda testifies, thirty people are going to do something about it,” Kasabian agreed and became the prosecution’s star witness.

The trial of Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten began on June 15 at the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles. Jury selection took five weeks. Bugliosi began his opening statement on July 24. In it, he summarized the events that had taken place at the Tate and LaBianca residences, gave a history of the Family and portrayed Manson as its undisputed leader to whom everyone deferred, and briefly described Helter Skelter and Manson’s general philosophies on life. He stressed that Manson had ordered the murders but that Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten had been willing participants in them, as evidenced by the excessive brutality with which they were committed.

The defense opted to give its opening statement after the prosecution had completed its case, so the prosecution began presenting evidence. Over the next twenty-two weeks, Bugliosi called eighty witnesses and introduced 320 exhibits. The true star witness was Linda Kasabian. She testified for a total of seventeen days and gave a detailed account of life with the Family at Spahn Ranch. She made it clear that Manson was in charge and dictated much of daily life, claiming at one point that “the girls worshiped him, just would die to do anything for him.” She spoke at length about Manson’s feelings on race, his belief in Helter Skelter, his obsession with the Beatles, and gave a very detailed account of the two nights of murder. Although it was brought out that Kasabian had at one point thought that Manson “was the Messiah come again” and that she was “controlled by…his vibrations,” she was a remarkably valuable witness. Her testimony was truthful, detailed, and consistent, and she sobbed openly when describing the murders and when shown pictures of the victims’ bodies.

Other witnesses included Family members and neighbors of the victims, the Polanskis’ maid who first discovered the carnage, William Garretson, Virginia Graham, Ronnie Howard, Steven Weiss (the eleven-year-old who found the gun in his backyard), representatives from the medical examiner-coroner’s office and various branches of law enforcement. Testimony also came from several people who had at one time known or been part of the Family, including Straight Satan Danny DeCarlo, Dianne Lake, a former Family member who testified that she had previously lied to the grand jury because she was “afraid that [she] would be killed by members of the Family if [she] told the truth,” and Barbara Hoyt, a Family member who testified in spite of an attempt by the Family to silence her by feeding her an LSD-laden hamburger. With the help of these witnesses, Bugliosi matched the knives and guns used at the crime scenes to those at Spahn Ranch, connected the bloody clothes found on the hillside to the defendants, verified the fingerprints found at the Tate residence as belonging to Watson and Krenwinkel, and established the whereabouts of the defendants on that fateful August weekend, all of which corroborated Kasabian’s testimony. He also elicited the details of Manson’s philosophy, connected him to the words written at the crime scenes, established that Manson felt he had to take Helter Skelter into his own hands, and introduced countless examples of his domination over the Family members. Finally, on Monday, November 13, the prosecution rested.

Kanarek had lived up to his reputation as an obstructionist. On the first day of Kasabian’s testimony he objected more than one hundred times. Reporters attempting to keep track of his objections quickly gave up the count. In the trial transcript, often ten or more pages separated Bugliosi’s question from the witness’s answer. Kanarek was held in contempt several times throughout the trial, but it did nothing to stop him from excessively prolonging the proceedings.

To the astonishment of all present, the defense rested immediately, declining to call any witnesses or present any evidence. Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten instantly stood, shouting and insisting that they be allowed to testify. Judge Older called a conference of the defense attorneys, who informed him they had rested because they feared that if they called their clients to the witness stand, they would take full responsibility for the murders in order to save Manson. Judge Older, however, ruled that the accused had a right to testify and that the three would have to be allowed to take the stand. But before they were given the opportunity, Manson insisted on speaking himself. Older allowed him to make a statement but removed the jury before allowing him to do so.

He gave a rambling, incoherent, two-hour speech, highlights of which included the claims that “these children that come at you with knives, they are your children. You taught them. I didn’t teach them. I just tried to help them stand up.” He also insisted that he “may have implied on several occasions to several different people that I may have been Jesus Christ, but I haven’t decided yet what I am or who I am.” When asked by Older if he wanted to repeat his statement in front of the jury, he declined, stating that he had “relieved all the pressure” he had. Upon returning to the defense table, he told the girls that they no longer had to testify and they immediately stopped clamoring to do so. With that, the defense again rested. After a brief suspension, closing arguments, and jury instruction, the jury left the courtroom to deliberate on January 15, 1971. After nine days, it returned and announced that it had found Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten guilty on all counts.

The guilty verdict was followed by the penalty phase of the trial. After another eight weeks of testimony, the jury deliberated again and re-emerged on March 29 to sentence all four defendants to death. They were immediately taken to prison to await their fates.

In addition to being one of the longest criminal trials in history, the Manson trial was also one of the strangest. Family members held a vigil outside the courthouse for the duration of the trial, waiting, as one young woman phrased it, for their “father to get out of jail.” They passed out flyers and shouted at passersby. Manson behaved bizarrely the entire time. On the first day, he arrived at the courthouse having carved an “X” into his forehead and his followers outside passed out a flyer in which he explained that he had “X’d himself from your world” (he later turned the X into a swastika). He constantly interrupted witnesses and made wild outbursts to the judge, jury and spectators, making proclamations like “you’re going to destruction, that’s where you’re going” and “it’s your judgment day, not mine.” He also threatened people, claiming that he “had a little system of [his] own” and that someone should cut Older’s head off. He once lunged at Older, brandishing a sharpened pencil, and another time threw paper clips at him. As the evidence accumulated and his guilt seemed imminent, he tried to smuggle a hacksaw blade into his cell and attempted to bribe a bailiff to help him escape. Older constantly had him removed from the courtroom and placed in a side room where he could hear but not interrupt the proceedings.

The girls were equally outrageous. They made protestations, and on one occasion stood up together and started chanting in Latin. Atkins once tried to grab a knife off of the evidence table. Another time she kicked a deputy in the leg and grabbed notes from the prosecution table, tearing them in half. They also copied Manson’s actions. When they saw the X carved on his forehead, they did the same to theirs. During the penalty phase, Manson shaved his head and the girls followed suit. When he was removed from the courtroom, they often were not far behind.

The antics of Manson and his followers might have been laughable had they not been truly frightening. It was clear to all involved that the Family had no reservations about using violence or following through on the threats they made, and they made many of the people around them more than a little nervous. Bugliosi began getting hang-up phone calls at home, even after he changed his unlisted phone number, and he was often followed by Family members when he left the courthouse. One day during testimony, Manson turned to a bailiff and told him that he was “going to have Bugliosi and the judge killed.” In response, Bugliosi had an intercom system installed in his home that would instantly connect him to the nearest police station and had a bodyguard accompany him for the remainder of the trial. Judge Older had a driver-bodyguard and 24-hour security at his home, and, after the day Manson lunged at him with a pencil, he wore a revolver under his robes. Atkins’s attorney Daye Shinn reportedly kept a loaded gun in each room of his house.

As it turned out, they were right to take precautions. Ronald Hughes, Van Houten’s lawyer, had been particularly opposed to letting her take the stand. She had only been present at the LaBianca residence so was only charged with two counts of murder rather than seven and thus had the most to lose if she sacrificed herself for Manson. After the defense rested, Older granted a ten-day recess in which the attorneys were to prepare their closing arguments. Hughes reportedly planned to use this time to go camping and work on his argument from the Sespe Creek in Los Padres National Forest, just outside of Los Angeles. When the trial resumed, Hughes had vanished. No one could locate him or had seen or heard from him within the past few days. When he failed to appear again the next day, Older assigned Van Houten’s defense to another attorney, Maxwell Keith, and granted his request for a three-week extension so that he could familiarize himself with the case before closing arguments began. Many, including attorney Fitzgerald, speculated that Hughes was dead. Weeks later, Hughes’s body was found in the Sespe Creek. Unfortunately, determining a cause of death was impossible because it had been submerged underwater for so long. Since there was no evidence of foul play, there was no investigation. However, one of the Family members allegedly said later that “Hughes was the first of the retaliation murders.”

The trial of Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten was one of the most ardently followed and highly publicized trials of all time. Not only Angelinos but people nationwide obsessively listened to, read up on, and talked about the case, the victims, the defendants, the attorneys, and the trial proceedings. They couldn’t get enough. On the Monday morning after the murders took place, TV programs were interrupted for updates and people commuting to work tuned their car radios from music to news coverage. Several of Sharon Tate’s movies were rereleased in theaters. Susan Atkins, before she rescinded her grand jury testimony, sold her story to the Los Angeles Times and, before the trial even began, it was published in paperback called “The Killing of Sharon Tate.” On the day of Manson’s arraignment, the courtroom was so crowded that Bugliosi would later write “you couldn’t have squeezed another person in with a shoehorn.” On the first day of the trial, spectators began waiting outside the courthouse at 6 A.M., just hoping to get a glimpse of Manson. Before a verdict was even reached, filmmakers went to work on a documentary on the trial, which, after completion, was shown at the 1972 Venice Film Festival and nominated for an Academy Award. To some, Manson became a cause célèbre. Shops sold tee shirts, posters, and buttons bearing his face, and the Family grew in numbers while he was in prison.

There were several reasons for the widespread interest in the case. First, it fed off the fascination many Americans had with hippie life and counterculture, from the drugs to the communal living to the kinds of people who partook in them. It also allowed those who were antagonistic towards this lifestyle to voice their concerns and apprehension. Although Manson never claimed to be a hippie nor did he espouse the hippie creed, which preached peace over violence, many identified him as one. These people felt that the murders were the dark consequence of going against established and mainstream living. As one author explained, the case “highlighted the growing rift between two generations of Americans.” Patt Morrison, columnist at the Los Angeles Times, wrote that the case showed the “dark side of paradise.” She wrote that because of it “people could shake their fingers and say, ‘this is where your high-living, rich, hippie, movie-star lifestyle gets you. This is where drug culture gets you.’ It’s the boomerang effect, the wages of sin.”

Second, the case exuded celebrity. At every turn there was a nationally identifiable name.

Finally, the crimes perpetrated by Manson and his followers were some of the scariest in recent memory, perhaps in the last century. They were truly the stuff of nightmares. The killings were gruesome, and the violence inflicted on the victims was beyond excessive. The victims were killed within the supposed safety of their own homes and chosen at random. Seemingly anyone could be next. The Family members, both those standing trial and those holding vigil out on the street, were odd and creepy. They had vacant expressions, spouted nonsense to passersby, and seemed to have no remorse for what had happened. Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten often smiled, sang, laughed and joked with reporters and spectators when led in and out of trial. They were so young and innocent looking, yet capable of such violence and terror.

On top of everything else, there was Manson, who by himself was a terrifying character and somehow had warped the minds of America’s youth and convinced them to kill for him. He constantly made startling statements, like “if I get the death penalty, there’s going to be a lot of bloodletting.” He was “the bogeyman under the bed, the personification of evil, the freaky one-man horror show.” So afraid of and focused were people on Manson that the case was commonly referred to as “the Manson case” rather than “the Tate case” or “the LaBianca case” or any other victim, as most cases are.

After Sharon Tate’s death, celebrities from Frank Sinatra to Tony Bennett to Steve McQueen went into hiding or increased their security measures. Even ordinary Los Angeles residents were frightened and fearful that they could be next. After the murders, a Beverly Hills sporting goods store reportedly sold 200 firearms over a two-day period, when before it had been selling three or four per day. Security companies around the city doubled their personnel. Guard dog breeders and sellers ran out of dogs. Accidental shootings dramatically increased, as did reportings of suspicious persons to police. Even with five defendants imprisoned, there were countless other Family members out on the streets, apparently capable of the same callous unfeeling violence and constantly being quoted as saying things like “there’s a revolution coming, very soon,” and “you are next, all of you.” Americans were terrified.

Yet they simply could not look away. The press capitalized on this widespread fascination. The story was simply everywhere. Coverage surpassed that of all previous murder cases other than the Lindbergh kidnapping and the assassination of President Kennedy, and had begun instantly. Having monitored police scanners, reporters were already gathered outside the Tate residence when the first police cars arrived, shouting questions as officers came and went; “Is Sharon dead?” “Were they murdered?” The first AP story went out before the names of the victims were even known.

The Tate murders made the headlines of the afternoon papers and were breaking news on television broadcasts not only in Los Angeles but nationwide. “Actress, Heiress, 3 Others Slain,” read the page one headline in the Washington Post. The New York Times carried a similar story, entitled “Actress Is Among 5 Slain At Home in Beverly Hills.”

With little concrete information, reporters published stories brimming with rumors and untruths. Some claimed that Sharon Tate’s baby had been cut out of her abdomen. Other’s claimed that the towel thrown over Jay Sebring’s face was a Klu Klux Klan hood. One investigator made the mistake of saying to a reporter that the killings “seemed ritualistic” and the story that ran in the Los Angeles Times was headlined “Ritualistic Slayings: Sharon Tate, Four Others Murdered.” Papers published long detailed accounts of the victims’ lives, noting Roman Polanski’s penchant for violence in his movies. In most cases, the implication was that these celebrities, with their high living and no-consequence attitudes, had brought their deaths upon themselves. “Live freaky, die freaky,” was the oft-quoted general consensus. The coverage was so negative that, on August 19, Polanski called a press conference to clear up some of the rumors and scold the most shameless reporters.

The LaBianca killings got similar coverage, capturing headlines and television banners on Monday morning. “Second Ritual Killings Here” cried page one of the August 11 Los Angeles Times.

The coverage continued even when there were no updates or promising leads and reporters were forced to grasp at straws. Life magazine filled its pages with photos of the crime scene. The “Tonight Show” featured Truman Capote, the noted author of “In Cold Blood,” discussing what he believed had transpired. Tiny details were described as “breakthroughs.” When all else failed, reporters blasted law enforcement for not making any progress. “What is going on behind the scenes in the Los Angeles Police investigation (if there is such a thing)?” asked the Hollywood Citizen News.

After Manson and his Family were identified as suspects, the press was reinflamed. The LAPD held a press conference on December 1 to announce the issuance of arrest warrants for Watson, Krenwinkel, and Kasabian, and over two hundred reporters representing publications and news stations from all over the world were in attendance. Afterwards, coverage focused mostly on Manson and his strange followers: their customs, their lifestyle, their history. No detail, if strange and shocking enough, was irrelevant. Reporters traveled to Inyo County and filmed the treacherous journey out to Barker Ranch to show how remote the location was. Unincarcerated Family members were interviewed, some so frequently that they were on a first name basis with the reporters, as were the parents, siblings, and past friends of the defendants. The New York Times published a massive article entitled “Charlie Manson: One Man’s Family” that spread over several pages and promised readers “a look at its members and their way of life.” The District Attorney’s office received more than one hundred press inquiry calls each day. Over one hundred reporters flooded the hallways on the day Atkins testified before the grand jury, and one publication reportedly offered $10,000 just to look at a copy of the transcript. Her story sold to the Los Angeles Times, and was reprinted in other publications across the globe. When the prosecution took Kasabian from jail so that she could show them the route she and the others had taken on the first night of the killings, they had to cut the outing short because they were followed by a television news van.

The press was so ubiquitous that it often beat out investigators when trying to get a story. It was a reporter attempting to identify the unknown victim in the white Rambler at the Tate residence who wrote down the car’s license plate number, checked it at the DMV, and traced it to Steven Parent. Similarly, it was a news camera crew, trying to recreate the events of that night for its viewers, that found the bloody clothes on the hillside. The gun was identified when young Steven Weiss’s father heard about the gun described in Atkins’s Los Angeles Times tell-all and realized that it matched the one his son found in the backyard.

So pervasive was the coverage that the first judge assigned to the case, Judge Keene, issued a gag order, forbidding anyone involved in the trial to speak to the press, and denied Manson’s request for a change in venue because, “even if warranted, [it] would be ineffectual.”

Knowing that the publicity would continue at this level throughout the trial, the jury was immediately sequestered and remained so for the duration of the trial. At 225 days, it was longer than any jury had been sequestered before. The case snagged newspaper headlines nationwide on the first day and every day in which there was dramatic or noteworthy testimony. Some stories were accurate, others were rumor-filled. In early August, President Nixon, commenting on the case, declared Manson guilty, and his statement was so widely published that the windows of the bus that shuttled the jury back and forth from the courthouse to their hotel had to be blacked out to keep them from seeing the headlines of papers on display at newsstands and being read on the streets. When the guilty verdict came in, the Los Angeles Times covered it in a special early edition released that afternoon.

After being sentenced to death, Charles Manson was sent to the state prison at San Quentin to await execution. Family members attempted to free him, claiming they planned to hijack a commercial airplane and kill a passenger every hour until he was released. They were unsuccessful. But on February 18, 1972, the California Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty, finding capital punishment “impermissibly cruel.” This decision worked retroactively, commuting all upcoming executions to life in prison. Manson was saved.

He was transferred to several different facilities before being sent to Corcoran State Prison in 1989, where he remained until his death in 2017 at age eighty-three.

The same Supreme Court decision that spared Manson also spared Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten. All three were transferred to the California Institute for Women at Frontera, where they have remained since. Van Houten appealed for and received a new trial in 1976 in light of the mid-trial disappearance of her attorney, Ronald Hughes, but was convicted again. All three women have renounced Manson and expressed deep remorse over what they have done. They have been exemplary prisoners at Frontera and they take their hearings seriously, but none of them have received parole. Atkins died of brain cancer in 2009 at age 61. Krenwinkel and Van Houten are still alive.

After being granted immunity, Kasabian returned to New Hampshire where she attempted to live a normal life. However, the media attention on her was so overwhelming that she took on an assumed name and disappeared. She spent twenty years living in hiding until a documentary film crew found her in 2009 living in a poverty-stricken trailer park.

Tex Watson was finally extradited and tried separately. He was convicted of all counts on October 12, 1971 and sentenced to death but, like the others, his sentence was commuted to life in prison. He is serving out his sentence at Mule Creek State Prison, where he has been ordained as a minister, claiming to have experienced a religious awakening.

Vincent Bugliosi remained in the legal profession but spent the majority of his time writing non-fiction. His book on the Manson case became a best seller. He died in 2015 at age eighty. Irving Kanarek suffered a psychiatric break down in 1989 and spent several years recuperating, during which he lost his law practice and the State Bar was forced to give $40,500 to former clients waging claims against him. He retired from the Bar and has not practiced since, still alive at age one hundred. Paul Fitzgerald remained in private practice in Los Angeles as a prominent and well-respected criminal defense attorney until he died of heart problems in 2001 at age 64. Daye Shinn was disbarred in 1992 for misappropriating client funds, and has died in the years since.

While Manson continued to attract twisted admirers, the Family has dissipated.

Yet even as the Manson saga came to an end, America’s obsession with it did not. There is something about the case that continues to captivate. Bugliosi’s book on the trial has sold seven million copies and was dramatized for television in both 1976 and 2004. When it aired, the 1976 version was the most watched made for television movie in history. A 1994 ABC special on the case received the highest ratings ever garnered for a network magazine show debut.

Manson received more mail than any other jailed individual in history and was continually sought out for interviews by the press. A wax figurine of him stands in Madame Tussaud’s in London. An opera titled “The Manson Family” premiered at Lincoln Center in New York in 1990. The popular television series “South Park” produced an episode called “Merry Christmas, Charlie Manson!” complete with Manson as an animated character. More than any other murderer, Charles Manson has become part of our cultural consciousness, a reference that everyone recognizes and understands whether or not they were alive to experience his trial. As one journalist writing on the 40th anniversary of the murders phrased it, Manson “remains a household name synonymous with evil, hatred, even the devil.”

While one of the most sensational trials of the century, it left no lasting legacy on our legal system. Even in his afterword to “Helter Skelter,” written 25 years later, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi offers none. If anything, the most outsized legal influence was the movement to reimpose the death penalty. Shortly after Manson’s conviction in 1971 the penalty was ruled unconstitutional in California in People v. Anderson, and Manson and the girls came off death row, their sentences reduced to life in prison. But at the time parole was possible after seven years for anyone serving a life sentence, and in 1972 voters approved Proposition 17, incorporating the death penalty into the California Constitution and obviating Anderson, and in that public battle Manson featured prominently.

The trial had, of course, a massive cultural impact, bringing an end to the Age of Aquarius and the counterculture of the 1960s. Manson became, and remains, the most famous criminal in America since Al Capone. Even those too young to have experienced the trial know Charles Manson as the face of evil, except those on the fringes who still worship him and wear his face on t-shirts. In his afterword, Bugliosi pointed out that in 1977 the police in California arrested the Trash Bag Murderer, one of America’s most prolific serial killers, who confessed to thirty-five murders and is suspected of many more. He shot, then sodomized, then dismembered his victims. As gruesome as Manson, Bugliosi remarked that no one remembers his name: Patrick Kearney. There is just something special about Manson.

Until his death in prison in 2017, Manson remained as outrageous as he was at his trial. In 1988, he told journalist Geraldo Rivera: “I’m going to kill as many of you as I can. I’m going to pile you up to the sky.” Laurie Levenson, professor at Loyola Law School, aptly said “I think Manson will haunt us forever.”

[Mark J. Phillips is a partner at the law offices of Lewitt, Hackman, Shapiro, Marshall & Harlan in Encino. Aryn Z. Phillips is a graduate of the Harvard School of Public Health and holds a Ph.D. in Public Health from UC Berkeley.]