Letter from Mykonos

[Editor’s Note: Aleka Dimou is a criminal defense lawyer on the Greek island Mykonos. Two miles offshore her home lies the floating island Delos, where according to Greek myth twins Artemis and Apollo, the Bonnie and Clyde of their time, were born of Leto. Artemis popped out first, and was such a quick study that nine days later she midwifed laggard Apollo’s birth.

These figures of myth were full-throated lusty creations. Hence the unusual statuary found thereabouts.

From these myths contemporary notions of criminal justice developed. The old gods still are celebrated throughout the Greek isles. Lawyer Dimou ramrods this year’s celebration, Delos 2015, this weekend. Fire up your private jet and go if you can.

What follows is Ms. Dimou’s script for the documentary, “Delos of the Gods,” premiering at the festival on Mykonos. Hide the children.]

The sun is lighting up a new world, still malleable, waiting to be formed. Over the waves there drifts a rock, floating along, without identity, nameless. Adelos. Unapparent… A plaything of the waves and the winds.

The rock casts no shadow because the rock it moves with the sun. It travels in a space without memory, beyond history, out of time. But look! A certain spot, an important moment. Somewhere—at a point in space and a moment in time the rock stops. It escapes the glaciers of oblivion (ληθη) and becomes reality, truth (αληθεια). It is now attached with diamond chains to the centre of the archipelago. It acquires a place in the world, its own space in the universe. And it has an identity. A-delos becomes Delos. The rock becomes an island. In the middle of the Aegean Sea it stops (ισταται) and looks around (ορα). It acquires a history.

It surrounds and is surrounded! It surrounds the imperceptible rift between Myth and History. And it is encircled by titanic guardians, by floating priestesses. The Cycladic islands. Small and large.

The island of escape becomes a shelter. There are shadows now and in the shade of a palm tree Leto, or Lato, will lie and rest. The daughter of Titans Koios and Phoebe who arrives in the guise of a she-wolf, a refugee from the Land of the Hyperboreans. Hunted by Hera and banned from giving birth on land anywhere under the sun. Poseidon is her saviour.

Leto hugs the trunk of the palm tree during her labour pains and, in the shade, brings to light the two archers. Artemis and Apollo. Nature and reason.

Here! In the sacred lake!

Apollo is the harmony in the world. He combats disorder and chaos, the darkness that gives rise to the forces of the underworld which threaten the universe. He loves symmetry, harmonious music and light. He could only have been born here, just here, where the light is harsh, exposing lies and untruths, causing the truth to shine.

And yet, few of the mosaics in Delos depict Apollo, rather they celebrate Dionysos. The God of chaotic forces, wild music, drunken orgies and passionate eroticism. The sexless God who wanders in the forests crowned with vine leaves, accompanied by maenads and satyrs, eating food raw and flirting incessantly, shamelessly and openly.

Is it perhaps possible that here, on this island that emerged from nothing to become something, on A-delos that became Delos, we are seeing the definition and merger, the relationship and the conjunction of chaos and world, of love and death, of eternity and time, in short, the real world?

Is it possible that here, for a moment or perhaps forever, under the pitiless sun, has been achieved the extremely frail equilibrium between opposite forces, which is called LIFE—EXISTENCE?

So the island that came out of nothing to become something, the (unapparent) A-delos that became (apparent) Delos, entered history. It abandoned the myth, joined the flow of events and acquired a living population. Next to the city of Gods spread the city of humans.

I wonder whether the sculptors of the marble harpists and the broad-hipped mother goddesses passed through here. Whether the Minoans with their narrow waists and vases decorated with octopus legs ever lived here. Did the ships of Menelaus or Ulysses pass through these open seas on their way back from conquered Ilium?

Countless people wandered through the narrow labyrinthine lanes and climbed the slopes of Mount Kythnos with its rich aroma of thyme and sage. They dug dark cisterns in the earth to collect the scarce rainwater. Their rich traders and ship-owners built two-storey mansions around courtyards with pebble floors and shady colonnades, offering protection from the pitiless sun. They opened shops selling food and fabrics; and created markets filled with goods from neighbouring islands and later, the whole Mediterranean.

The soil of Delos, sacred and inaccessible, could not be used for farming or the keeping of herds. Animals never grazed this land.

And it was more than the cloths and pots of merchants that converged on Delos to be sold. There were also people, captives gathered from the whole of the Aegean to fill the renowned slave market that was organised there. Later, when the city had grown, away from its narrow lanes and busy markets, beyond the avenue with the ceremonial lions of the people of Naxos, the theatre was built.

I wonder how: blinded Oedipus’ screams, Hecuba’s laments, and Medea’s curses sounded, as they echoed up the slopes of Mount Kythnos. How men, gods and heroes — trapped in the nets of a blind destiny, and succumbing to the consequences of their hubris — appeared before the eyes of a public moved to tears. Until hearts softened through catharsis and a just ending. Until the public felt that Justice is not a remote and abstract notion, is not a virtual sun but a real force and therefore reassuring.

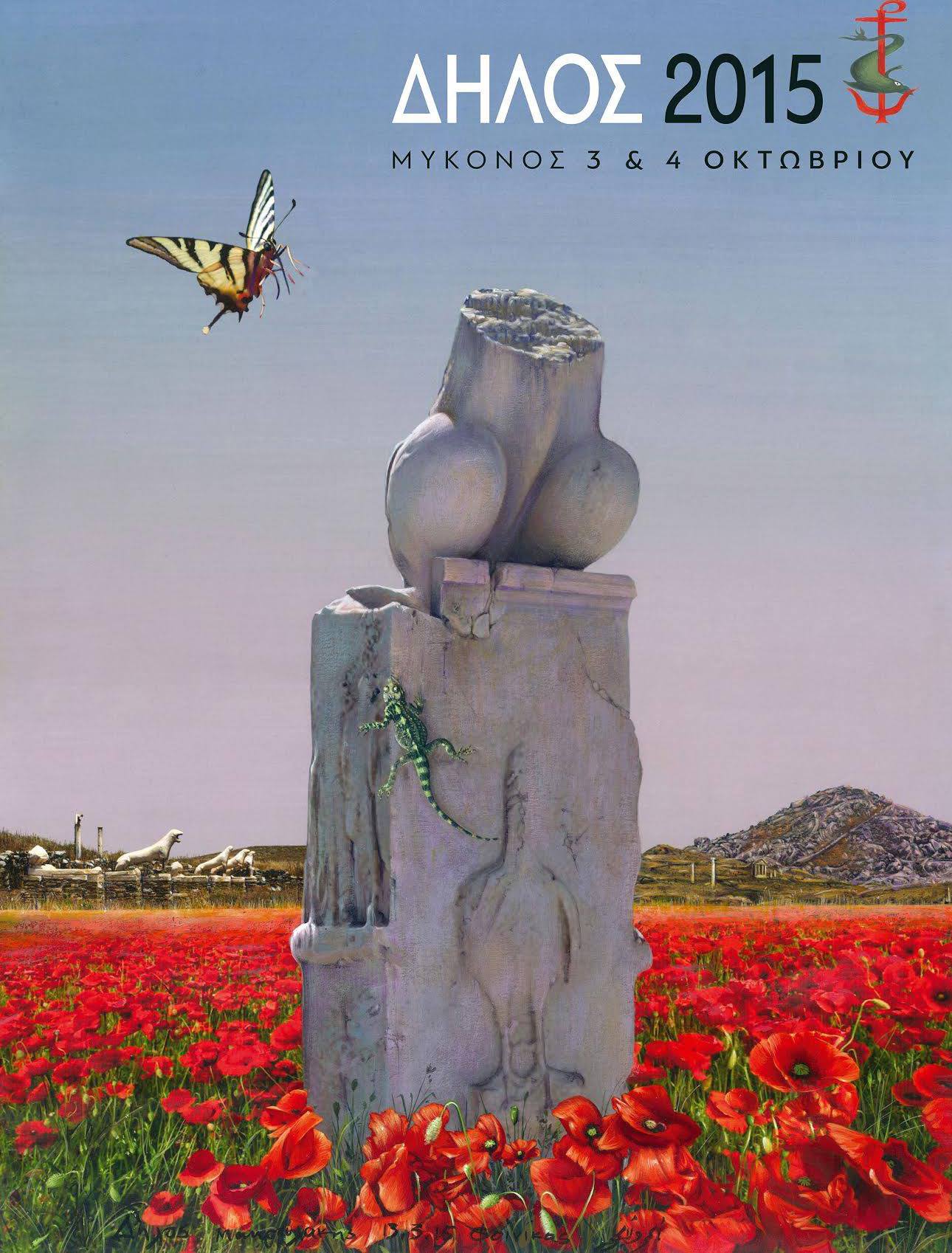

All around, the drystone walls of the houses, some remnants of plaster in the children’ room engraved with a wish or a prayer, the first rude letters. Here and there, a marble column or a stone threshold without a front door, drowned in camomile and red poppies. And so, what was minor becomes major, light matters become weighty issues — hence the stone threshold is found worthy and this world, the poet’s small world, becomes great.

The great temple, the sacred buildings, the altars for worship face the turbulent sea— the terrible Tsiknias passage — under the bright sunlight, these are the space of the gods, beyond time and history immersed in the calm silence of eternity.

The space of gods, on the one hand, calm and serene; and the city of humans on the other, agitated, labyrinthine, full of intensity and pathos. The realm of mortality and of love, which is the only escape from death. It is love that differentiates the city of the humans of Delos from the one opposite, the calm and serene city of the immortals, of the gods. Between the two the phalluses of Delos mark the boundary between the space of Apollo and the space of commerce. They stand high on their pedestals, trying to penetrate the sky, bold, arrogant and persevering as if in a sexual embrace.

Mother Earth raises her phalluses to inseminate the sky, ejecting fountains of seed into the clouds of the virile and hard primeval element.

Delos the hermaphrodite.

Delos the androgynous.

Humanity is the ideal model for Plato’s earthly love — man is not biblical, angelic and sexless, but demonic, active, creative, self-sufficient and pleasure seeking.

The phalluses of Delos stand as a monument to pleasure: pleasure that shatters into thousands of heartbreaks; pleasure crushed by death; pleasure without the blissfulness of godly immortality. Pleasure as the cure, the ELIXIR and the POISON of consummated eroticism —unashamed in its nudity.

Pleasure: rude and shameless.

(The narrator remains in the theatre, standing, immobile on the stage).

Is man his own master? Or are his actions determined by his human destiny? Is he the free ruler of himself and his own lot, or is he at the mercy of blind fate? Is he proud Antigone, convinced that she is obeying a godly, higher code of ethics; or is he Medea indulging her love’s passion? Or is he perhaps Oedipus, victim of the curse haunting his predecessors? Oedipus who was convinced he acted virtuously and did not commit the vilest of crimes.

Is man the only being that doubts, questions and contests or does he just obey and suffer?

Are these the human heroes: who blithely ignore the factors that will defeat their efforts? Who also ignore their inner world, and are thus led to hubris, to the end of the drama, to death.

Death always shatters life.

Or are they the heroes who question even death, the only certain end, presaging a resurrection of the dead? Even the recently buried dead, like those that the Athenians dared to exhume in 424 BC during the “cleansing” of Delos and take to Rhenea, to a common grave. After that, women in confinement and the dying were forbidden to stay on Delos, the latter were sent immediately to Rhenea. Adelos, Delos, Delos of the humans, Delos of the Gods could not be host, neither to confined women nor to the dead. The inhabitants of the island became mere tenants, due to the barbaric behaviour of the Athenians which blackened Pericles’s Golden Era.

(The narrator sits on a piece of marble in the middle of the auditorium).

The priest of Dionysos used to sit here.

Hadrian also sat somewhere here on that autumn morning when he visited Delos coming from Ephesos, inspired by the spirit of Apollo, rational thinking, symmetry and harmonious chords.

Did he see the Bacchae?

Did he discern Pentheus and his subterfuge?

Did he think about his destiny?

Somewhere close to here, where the marble becomes smooth like flesh, Antinoos must have sat, the divine boy whose statues filled the world, from Gibraltar to Mesopotamia and from the Nile to the coasts of the English Channel. Antinoos who was loved, not for his wisdom nor for his bravery, but for his beauty.

The beautiful boy, whose starry constellation passes often above Delos and sheds its pale light onto these marbles.

Lower down is the sea and the harbour with the cedar yacht ready to carry the couple away, tragic figures in a drama four centuries after Euripides. Away somewhere, no matter where, perhaps to Athens, to Sicily, to Rome, wherever their fate leads them.

And now we are here, in a drama played thousands of years later. A drama of agony and fear where our illusion is that we will escape death.

Our journey is full of fear, death and love, love and death and its duration is uncertain. But, in truth, the destination is known.

(The narrator climbs Mount Kythnos, looks out from the top to the sea around and the 24 Cycladic islands. He breathes deeply, enjoys the beauty, the beauty of Delos, the beauty of the sea, the beauty of the world).

This high peak, is it the starting point or is it the destination? Is it the origin, is it the beginning or is it the end of a nostalgic journey? How beautiful life is; how unjust are sleep and death; how magnificent the overcast sky, no longer golden, but leaden, how beautiful the sun and the wine dark sea roughened by a threatening storm.

(The world of 2015.Views, the 12 year old boy killed by policemen in America, in Cleveland, some other not terribly violent view from Greece. And the narrator can only be dreaming. Dreaming is the only salvation line and the only way out to hope beyond reality.)

Below us the world that emerged from chaos. The A-delos Delos. The island that became something from nothing. And even if death and sleep are waiting round the corner, dreams accompany them.

Dream IS indeed the only possible obstacle to Death. Death can only be overcome in dreams. Only then does death become a-delos and mortals become immortal…

The dream of the mortal and perishable human being is nothing else than the desire of immortality…

It is the reminder of his divine origin; it is his inheritance along with Art, Creation, Love and Freedom.

The dream to leave behind here at the PEAK, be it the origin or the destination, his trace, the seed of his immortality. Here on the peak of Delos.

A-delos Delos.

Delos, Delos 2015

[Translated from the original Greek by Ms. Dimou’s friend, Styliani Profis]